Mother Jones; Instagram; Wikimedia

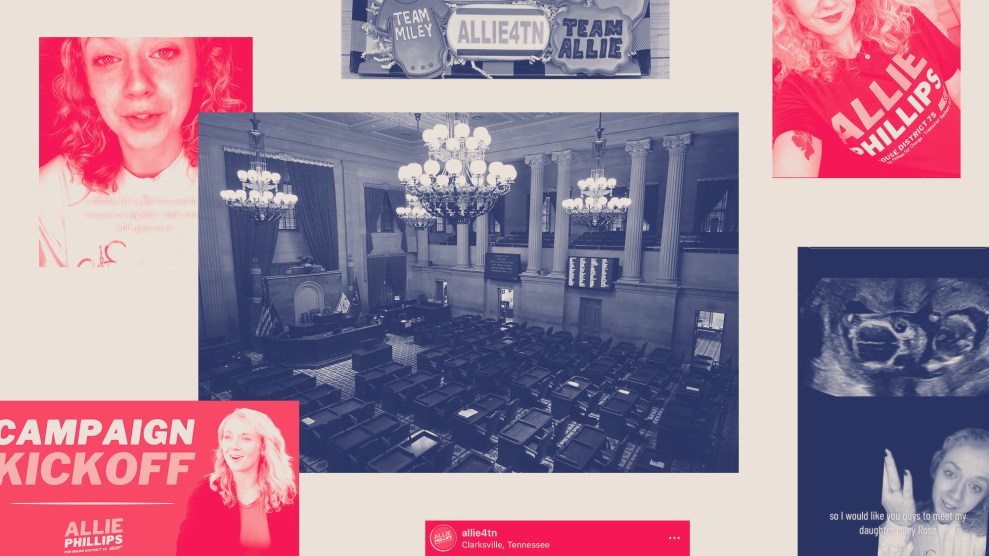

Allie Phillips, a 28-year-old running as a Democrat for the Tennessee House of Representatives in District 75, has told her abortion story countless times. She has explained it to her followers on TikTok, to the lawyers helping her sue her state over restrictions to reproductive care, and to the lawmakers who failed her.

In November 2022, Phillips found out she was pregnant. She and her husband were setting up their lives to welcome another girl into the family, Miley Rose. Over the following months, Phillips shared her entire pregnancy journey on TikTok. It began with screen-recorded FaceTimes of her family and friends seeing the positive test on the counter. Then, after her 19-week appointment, Phillips posted another update: “You can probably tell by my face and the mascara on my shirt, I don’t come with good news.”

Doctors found several anomalies. Tests showed that the fetus had developed semilobar holoprosencephaly, a rare disease where the brain has only partially divided into two hemispheres. There were also problems with the kidneys, bladder, stomach, and heart chambers. No amniotic fluid. No sign of lung development. No growth since 15 weeks. The fetus likely wasn’t going to make it to birth. If Phillips got to that point, chances of survival were slim. The longer she stayed pregnant in this condition, Phillips’ doctor explained, the more her health was at risk.

At the time, Tennessee’s trigger ban was in place, which made performing an abortion a felony, with no exceptions for rape or incest. Doctors could use an “affirmative defense,” the law said, to prove that the abortion was necessary to prevent death or “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function” of the pregnant person. Like other life of the mother clauses across the country, this “exception” is medically confusing for providers. It also leaves out women like Phillips—she wasn’t bleeding out on a gurney yet. “My doctors and I don’t know what the life of the mother means,” she told me.

Then, Phillips said a phrase I’ve heard her say countless times online. It’s at the center of her candidacy, her story, and Miley’s Law—legislation that she hopes to pass in Tennessee to give the power to pregnant people to decide their next steps when the fetus is diagnosed with fetal anomalies. “Every pregnancy is life-threatening,” she explained.

This is Phillips’ thing: Normalizing conversations about pregnancy, abortion, and loss. In doing so, she is showing another way to appeal to voters. For years, Democrats hid their politics on abortion behind vague phrases, which led in part to harmful state-wide policies restricting access before Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. Phillips is doing the exact opposite by embracing abortion as an issue that can win—and not mincing words on social media. She sees no contradictions in posting a video about her outfit to see Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour and then immediately responding to a comment that tells her she’s a murderer for her abortion. This is the normal life of a woman.

In some ways, she’s following in the footsteps of a lot of other women in politics. Senator Elizabeth Warren made universal childcare one of her main 2020 presidential campaign running points after detailing how her Aunt Bee had to come watch the kids. Senator Patty Murray ran decades ago as a “mom in tennis shoes” and now she’s third in line for the presidency. Women have run for office after losing a child to gun violence, like Representative Lucy McBath in Georgia. But it also comes at a unique time. In the 2022 midterms, despite fears of a red wave, the Supreme Court’s decision to repeal Roe v. Wade spurred voters to support Democrats. Voting on measures in California, Michigan, Vermont, Kentucky, Montana, and most recently Ohio, Americans came down on the side of abortion access.

Phillips exists at a new, modern intersection: as someone who not only fell victim to an abortion ban in their state, but survived to tell the tale online, and is choosing to run on her experiences living in a post-Roe America.

The US is a uniquely dangerous place to be a pregnant person, and that was true even before Dobbs. The US maternal mortality rate for 2021 was 32.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, more than ten times the rates of other countries like Australia and Japan. Maternal mortality is on the rise in America—particularly for Black women, who are around three times more likely to die of a pregnancy-related cause. As Dr. Warren Hern, a physician and epidemiologist who specializes in abortions later on in pregnancy, wrote in the New York Times: “A woman’s life and health are at risk from the moment that a pregnancy exists in her body, whether she wants to be pregnant or not.”

Phillips was a part of an often misunderstood and ridiculed group of people who choose abortion in a wanted pregnancy for medical reasons. While conservatives try to tout that abortions up until the moment of birth are common—and even happen “post-birth”—procedures later in pregnancy are rare (about one percent). People often terminate at this time because they didn’t know they were pregnant, lacked proper insurance or information about access, were high-risk for life-threatening conditions, or found fetal anomalies, according to a multiyear study.

After she discovered the anomalies, Phillips went to New York. And she kept posting. “So I’m at the clinic right now,” Phillips says in one TikTok from that time. In it, she is sitting on the floor in the New York City office, moments after hearing that Miley’s heartbeat wasn’t there anymore. “She’s already passed,” Phillips repeated between sobs, as she held a soaked tissue. After telling the story so many times, she can mostly get through it, but Phillips said that moment still “breaks me apart.”

“I cry every single time,” she told me. “It’s easier for me to share the before and after details. Because though traumatic, they weren’t nearly as dramatic as that point when I was alone, finding out that my daughter was already gone.”

Shortly after returning from New York, Phillips was approached by the Center for Reproductive Rights to join other women who are suing their states for not providing life-saving health care. (The lawsuit is ongoing, and Tennessee recently filed a motion to dismiss the case.) She also met with her eventual opponent: state representative Republican Jeff Burkhart. Before joining the Tennessee House, Burkhart was on the Clarksville City Council for a maximum of twelve years. His campaign website listed some of his priorities as “Fiscal Sanity,” and “Crime Reduction.” In 2022, he won with just about 7,000 votes and no challenger.

A friend with the Montgomery County Democratic Party set up the meeting between Phillips and Rep. Burkhart, which lasted about two hours. They discussed fetal anomalies and what it was like to have to leave the state for care. But Phillips says it was clear he did not fully understand the issue.

Rep. Burkhart had been curious about her first pregnancy, and if it was “successful.” He then sounded surprised and implied that first pregnancies were the ones where problems, like miscarriages, took place. “I’m just a guy,” he said, according to materials reviewed by Mother Jones, but “most time the pregnancies that go bad are usually the first pregnancy.”

Phillips was shocked, and mad.

Still, she tried to work with Rep. Burkhart, who agreed to sponsor Miley’s Law. “He was like, ‘Well, you have 99 seats to pick from. It doesn’t have to be me,” Phillips remembered. “I was like, ‘But, you’re my representative. So I would like for you to sponsor my law.’” They took a photo together, arm in arm.

She texted him that day, saying she hoped that they would be able to make Miley’s Law a reality for other women in Tennessee. Rep. Burkhart said it was a pleasure and that he looked forward to working with her. A week later, Phillips checked in to see if he’d been able to set up that meeting with the Attorney General that they agreed to. He replied that he’s working on it. She followed up a couple more times that month. He said he was still working on it. A month passed, and it was late July. Are we any closer? she asked. He was still trying to get a meeting, he said, but the law they had passed in April, a thin exception, was probably it for now—at least until the next session in January.

“You said that you support the life of the mother if the pregnancy were causing risk,” Phillips texted Burkhart in response. “Well, every pregnancy is life threatening. A perfectly healthy pregnancy can turn deadly in a moment.” They haven’t spoken since, according to materials reviewed by Mother Jones. “Why am I sitting here relying on a man to help me?” she recalled thinking at the time. “I can do this myself.”

That was when she decided to run for his seat. “We have these laws [in] place because these men like Jeff Burkhart,” she told me.

Burkhart did not respond to Mother Jones‘ request for comment.

In the week following her announcement, Phillips said she had already received a donation from all 50 states. And she’s been written about in multiple national outlets. When I asked Phillips what she’d want to say to him now, should they end up on the phone or sitting in that same office where they met in June, she was quick to respond: “Good luck.”

While combing through Phillips’ TikToks, one stood out from July 19th, months before she would announce that she was running and be met with national attention. She’s sitting outside her house as thunder and rain fill the space and words fade on and off the screen. “Today is my due date,” it reads. “I’m doing my best for you,” she says out loud. Phillips isn’t looking at the screen. “I’m gonna make sure everybody knows your name.”

When I asked her about that video, Phillips said it was a particularly hard day. She considered laying in bed crying. “What good is that gonna do?” she decided. “So like, let me stay busy.”