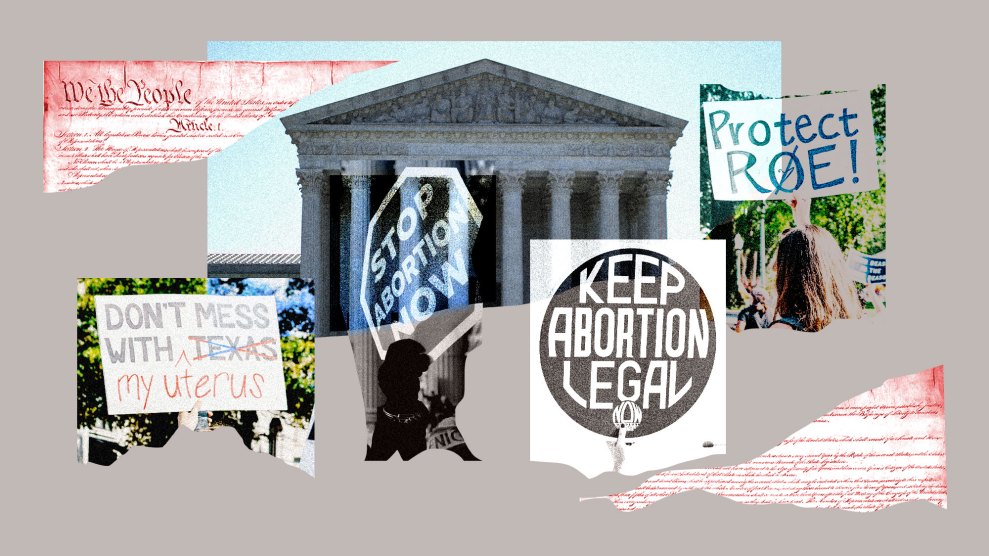

SUZANNE CORDEIRO/Getty

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court of Texas heard arguments in a suit brought by the Center for Reproductive Rights challenging the state’s abortion ban—the case could have ripple effects across the country as state courts wrestle with exceptions to abortion bans after the fall of Roe.

The Center for Reproductive Rights, representing 20 patients and two doctors, is asking the court to reconsider the medical exception language that currently exists in Texas’s abortion ban. The state’s law calls for “reasonable medical judgment” and permits abortion if the patient could die or if they’re at “serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function.” The lawsuit argues this language is too vague and dangerous for pregnant people and providers.

The organization has brought similar suits in Tennessee, Idaho, and Oklahoma. But the Texas one marks the first time that directly impacted pregnant people have sued their state over a post-Roe law.

These challenges are drawing attention to the thin exceptions that have accompanied abortion-restrictive laws. Often referred to as “life of the mother” exceptions, they act as vague asterisks that tend to leave patients and providers confused, resulting in a diminished standard of care for pregnant people.

“While there is technically a medical exception to the bans,” Molly Duane, the senior attorney for the plaintiffs, said in the arguments this week, “no one knows what it means and the state won’t tell us.”

This past August, a district court judge ruled that the state’s near-total abortion ban could not be enforced in pregnancies with certain levels of complications, including those with lethal fetal diagnoses. Texas’ supreme court justices, all of whom are Republican, are deciding whether or not they will side with the state or uphold the lower court’s ruling. The latter would signal that challenges to unclear medical exceptions may work in the future.

Decisions about life-saving healthcare have become increasingly complex and uncertain since Roe was overturned—and even before then in Texas. The state’s six-week abortion ban dates back to 2021 and set a nationwide example for how to criminalize providers. The OB-GYNs in the Texas case have said that the state’s exception has led to “widespread confusion among the medical community” that left them and their colleagues unable to do their jobs well. And if providers misinterpret exceptions and perform abortions that do not fall under the rules, the stakes are high; medical professionals risk prison time, fines, and the potential loss of their licenses.

It’s unclear how much clarity the justices’ decision, which Duane expects this summer, will provide for pregnant people and medical teams across the state. Until then, more plaintiffs are coming forward to ask where their pregnancy story fits into the law.

Many of the plaintiffs bringing these cases across the country, including in Texas, wanted these pregnancies. Some long-dreamt of being parents only to face devastation when hearing of fetal anomalies or health complications during a regular check-up. The appointments in question usually take place after 18 weeks of pregnancy and abortion bans’ week-based cut-offs are often before that time. These circumstances leave pregnant people and their families with little time to mourn before figuring out how to move forward.

The women suing the state of Texas had to make these tough decisions, and quickly. Some left the state for abortion care, while others gave birth to babies who only lived for seconds. Others were told to wait until they were in graver danger before the hospital staff would provide care.

“Politicians in Texas are prohibiting healthcare that they don’t understand,” Lauren Miller, one of the original plaintiffs said at a news conference this spring. “They could do something. But they’re not. And it’s killing us.”