When the US targeted Russia’s oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine, the trail of assets kept leading to our own backyard. Not only had our nation become a haven for shady foreign money, but we were also incubating a familiar class of yacht-owning, industry-dominating, resource-extracting billionaires. In the January + February 2024 issue of our magazine, we investigate the rise of American Oligarchy—and what it means for the rest of us. You can read all the pieces here.

The most profitable, and perhaps most dangerous, factory in the United States is a two-story, off-white block about 20 minutes north of central Fort Worth, Texas. It resembles many of the other buildings in a rather barren suburb along US 287, and, had there not been a large sign inviting passersby to visit, I would have driven past without a sideways glance.

Inside, it looked no more remarkable. A man in a Carhartt T-shirt and baseball cap walked slowly across the patched concrete floor; a woman with a blond ponytail in a black scrunchie jacked up a pallet; union T-shirts bearing the word “Solidarity” were the most common item of clothing. There was an unfamiliar smell: Imagine a new car filled with the hot air from a vacuum cleaner.

A half-dozen or so of us visitors looked down onto the shop floor’s battery of cream-painted printing presses from a glass-enclosed walkway. Had we been unaware of what the factory makes, we would have struggled to grasp it, for the printers worked at astonishing speeds, spitting out up to 10,000 sheets an hour in a green-gray-black blur. But the machines’ operators moved at a human pace and, when they stacked the sheets into piles, the nature of the product was obvious.

This enormous shed is the Western Currency Facility, one of the federal government’s two money-printing operations. (If “FW” is printed in small letters on the corner of a bill, it was printed there.)

The WCF produces more than 14 million banknotes a day. To keep up with the insatiable demand for dollars, it has invested in Super Orlof machines, which can print 50 bills simultaneously. The facility is set to gain an extra 250,000 square feet of floor space to ramp up capacity.

In one way, this is all as it should be. When Congress created a central bank in 1913, it aimed to bring order to the nation’s erratic monetary system. Back then, banknotes were scarce when there was high demand, such as at harvest time, meaning interest rates went up and the economy suffered. The new Federal Reserve tasked with creating currency “elastically,” with the explicit instruction to contract or expand the money supply based on demand.

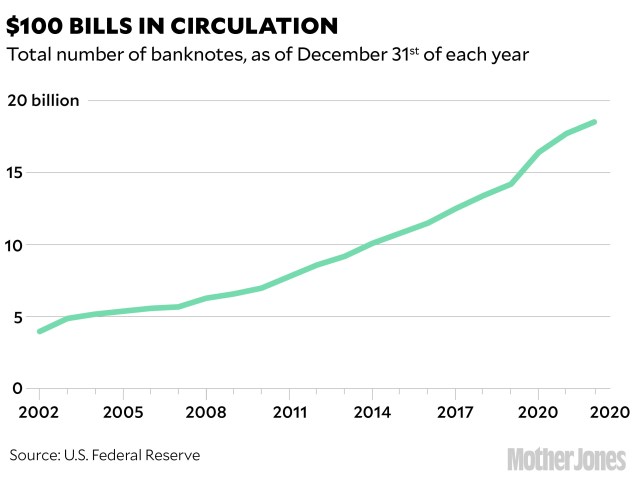

In October, $2.33 trillion worth of banknotes were in circulation, more than triple the amount two decades ago. This is a testament to the effectiveness and innovation of the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which runs the Fort Worth site. But in another way, this apparent success story is alarming, because it highlights how incurious officials (including lawmakers with oversight authority) have almost always failed to ask two key questions: Where are all these dollars going? And who’s using them? Because they’re not being used by ordinary Americans, and they’re not in the United States.

Surveys from Pew Research Center show a consistent decline in cash usage, with more and more Americans shopping online, using Venmo, and scanning their phones when they buy a coffee. Two-fifths of Americans use no cash at all in an average week, up from a quarter in 2015. The proportion of people who exclusively use cash has dropped accordingly, to fewer than one in seven, and when they do use cash, the transactions are smaller.

This is not purely a US phenomenon. The paradox of cash usage falling while cash demand rises was identified by Andrew Bailey, then the Bank of England’s chief cashier, in 2009. A similar trend is visible in the European Union. Central Bank officials have made various suggestions about who is using all these banknotes, normally derived from macroeconomic theories, but they rarely tackle the obvious explanation: The primary customers for their product are criminals, and the explanation for rising demand is a growing criminal economy.

America is an outlier from its Western peers in one crucial respect. In Britain, the largest share of the outstanding currency is made up of 20-pound notes, which are widely used; in the eurozone, likewise, it’s the omnipresent 50 euro banknote that is most often printed. In the United States, however, it’s the $100 bill, which most Americans rarely encounter. ATMs typically don’t dispense them; shopkeepers regard them with suspicion. Whoever is using them, it’s not ordinary Americans.

The $100 bill overtook the $1 bill as the most common denomination six years ago, and the trend has accelerated since: At the end of 2022 there were 18.5 billion $100s out there, and the Treasury Department printed another 1.5 billion in 2023. Of the total value of currency in circulation, 80 percent consists of notes with Benjamin Franklin’s face on them. Tracing bills in circulation is tough. But in 2017, Ruth Judson, a Federal Reserve economist, tried to answer the question of where they’re going by comparing statistics for US and Canadian dollars. Her conclusion was that about three-quarters of all $100 bills were outside the United States. If the trend she identified has continued, that total would now be more like 80 percent.

But who are the foreigners who want these banknotes, which are universally accepted and can’t be traced? Kleptocrats, tax dodgers, and cartels; anyone who has money to move in bulk, and scrutiny to avoid. And why do they prefer $100 bills? A million bucks in $100s weighs 22 pounds, five times less than the same amount in $20s. If you have a lot of currency to move, you want it to weigh as little, and take up as little space, as possible.

When US politicians first became concerned about money laundering, back in the late 1960s, the connection between crime and cash was so widely acknowledged that congressional committees regularly heard about private jets shuttling loads of currency to Caribbean tax havens, Hong Kong, or Switzerland. Eventually, in the 1980s, their concerns translated into concerted international efforts to tackle money laundering. And if you look at a graph of US currency in circulation, that is also precisely when the line showing the production of $100s begins to rise. As the financial system became more sophisticated in subsequent decades, journalists tended to focus on the latest tools available to criminals, which at the moment are cryptocurrencies. But their use is minuscule compared with paper money. In fact, as checks on digital money transfers have become more onerous, criminals have relied on the one form of currency that can’t be found on a spreadsheet: cash. (I asked officials at the Fed and the Treasury Department for comment; they declined or did not respond.)

“There is little question that cash plays a starring role in a broad range of criminal activities, including drug trafficking, racketeering, extortion, corruption of public officials, human trafficking, and, of course, money laundering,” wrote Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, in his 2016 book, The Curse of Cash. “The fact that large notes are used far more for illegal activities than legal ones long ago penetrated television, movies, and popular culture. Policymakers, however, have been far slower to acknowledge this reality.”

The unfortunate conclusion is that, by issuing this huge volume of $100 bills, the Fed is helping the world’s worst people evade law enforcement. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers seems to agree. In 2016, he wrote that a “moratorium on printing new high denomination notes would make the world a better place.”

Even so, no US officials appear to be clamoring for such a move. By printing “$100” on a piece of paper, at a cost of around 9 cents, the federal government makes it worth $100—which is why the WCF is the most profitable factory in the United States. Fed officials would be quick to point out that they are not technically making a profit of $99.91 every time they print a Benjamin, since the bill can be redeemed at any time. But as Fed official Christopher Neely wrote in 2022, “If the cash never comes back to the U.S., then Americans have just exchanged pieces of green paper—which cost almost nothing to print—for valuable goods. This is a good trade for Americans.”

That’s an understatement. The benefits from printing so much cash are colossal for the government. But the costs, almost entirely paid by victims of crime, tax evasion, and kleptocracy, are commensurate. Perhaps we should be asking ourselves whether this trade-off is worth it.