Mother Jones illustration; Random House; Thea Traff

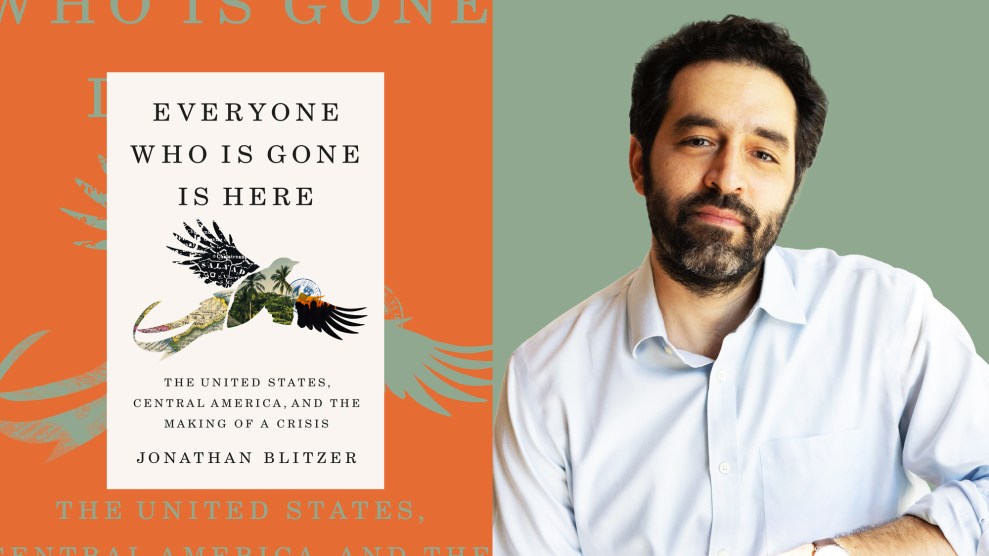

The New Yorker staff writer Jonathan Blitzer first heard of Juan Romagoza when the doctor was the main plaintiff and lead witness in a human rights case in Florida in the early 2000s. Romagoza had been the victim of abominable brutalities by the military rule in his home country of El Salvador when in the 1980s a right-wing government backed by the United States cracked down. On suspicion of being a guerrilla commander, the military in El Salvador tortured Romagoza; he was shocked, sodomized, burned, and then placed in a coffin for 48 hours. After an uncle in the military interceded for his release, Romagoza fled to Guatemala—another country where US policies of anti-communism meant propping up horrific rulers—and then migrated to the United States, where he became a major player in the sanctuary movement.

Romagoza’s story shows the history lost in the headlines about a border crisis and it drives Blitzer’s book, Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here: The United States, Central America, and the Making of a Crisis. “The only way I’ve come to understand this over the years is to try to make human sense of what every aspect of this broader drama has been,” he told me. “It was never academic to me. It was always intensely personal.”

Romagoza, and many others in Blitzer’s book, serve as a living testament to the often ignored ways in which US foreign policy helped shape the very conditions driving migration from Central America today. “Politics is a form of selective amnesia,” Blitzer writes in the introduction of the book. “The people who survive it are our only insurance against forgetting.”

Mother Jones spoke with Blitzer about the fraught legacy of the United States’ involvement in Central America in the name of fighting communism, the politics of the border debate, and why immigration might be a “democracy” issue in the 2024 presidential elections:

Throughout the book, you put faces and names to the many people—migrants, activists, faith leaders, bureaucrats—who embody how Central America and the United States are intertwined. Why was that important to you?

My feeling surveying this history, the politics, and the policy, is it’s all through and through so personal.

It’s very complicated writing about Latin American history and immigration policy because a lot of people know a lot of strands of the story without necessarily having put it all together. In the telling of immigration stories, everything is so fraught politically, and in journalistic contexts, everything is so immediately related to questions of policy or politics in Washington at a given moment. I wanted to restore in readers a sense that this is an epic human drama.

There’s a lot of history in this book that has often been left out of the conversation. You trace the roots of humanitarian crises at the border back to 1980. Can you talk about how the Cold War and US foreign policy of anti-communism connects to what is happening today?

The 1980s is a kind of logical starting point for this book because you have two things happening simultaneously.

One is the Cold War, where the United States is partnering with repressive right-wing military governments across the region, who are committing all kinds of brutal atrocities because the United States is preoccupied with the prospect of the spread of leftism and communism. You have that happening in very dramatic human fashion in places like El Salvador, Guatemala. At the same time, you have in 1980 the codification of asylum and refugee law in an American statute for the first time. It is a moment of the country finally trying to reckon with a legal and moral obligation to provide protection to people in need.

The two realities are fused together such that American foreign policy is almost incorporated into the DNA of American immigration law. From the very beginning, you had the asylum system—and immigration law more generally—getting co-opted by foreign policy interests.

People arriving at the southern border fleeing El Salvador and Guatemala, who had very strong asylum claims were denied asylum. Not because their cases weren’t strong, but rather because the United States government couldn’t acknowledge that the governments it was propping up and supporting in the region were committing the kinds of atrocities they were. The United States was helping create a new global demographic—a new population of people fleeing their home countries in Central America—as a result of these ongoing civil wars. At a certain point, a quarter of the Salvadoran population had fled to the United States. And yet, the legal mechanisms meant to exist to deal with the flow of people arriving at the border and integrating themselves into communities across America wasn’t up to the task.

The drama we see playing out in the 1990s and early 2000s is American policy trying to disentangle all of the interconnectedness that had solidified for decades—as a result of American policy. There’s this immediate circularity to how that stuff plays out.

And amid the cyclical crisis, the US is trying to address it with the same failed deterrence and consequence-driven policies…

Absolutely. Everything gets reduced the closer you get to the United States border. So there are deterrence policies at the border, which don’t take into account the inevitable fact that people who are desperate are going to come to the United States regardless of how harsh policy is at the border. And it totally neglects the pressures and factors in the wider world that no immigration policy can adequately address unless we look at them holistically.

Does the history of US interventionism in Central America help explain why Vice President Kamala Harris has struggled with the unforgiving task of addressing root causes of migration from Central America?

One of the effects of all of these years of American intervention, and then neglect, is that the region itself has been kind of upended.

By the time Kamala Harris arrives on the scene, you had the Honduran government in the final months of the regime of Juan Orlando Hernández—who ends up getting extradited from United States for drug trafficking (which the United States knew about for years but looked the other way because he had vowed cooperation on immigration related issues). You can’t easily engage with the government of El Salvador because at that moment, and now, you had a kind of strongman authoritarian president. And that left Guatemala, which also was famously corrupt (but was the least unsavory of the regional options).

How did we wind up in a position like this? This is the consequence of the previous administration withdrawing support for an anti-corruption body in Guatemala. And of the United States making allowances under Trump for increasing abuses perpetrated by Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. And successive Democratic and Republican administrations looking the other way on the corruption across Central America.

Regional partners are understandably wary and cynical about what it means when the United States says it’s going to roll up its sleeves and try to engage.

In the book, you talk about how in the 1970s the number of migrants crossing illegally into the United States was climbing. It was also a time when refugees from countries like Vietnam and Cambodia were coming here. During that era, the leader of the Immigration and Naturalization Service under Nixon talked about a “growing, silent invasion of illegal aliens” and the head of the CIA called the influx of Mexicans a “greater threat to the future of the United States than the Soviet Union.” It doesn’t sound all that different from what we hear today from right-wing anti-immigration hardliners and segments of the GOP…

It’s incredibly striking to see some of the same language used, but just ratcheted up in volume. It shows you why a cynical appeal on immigration continues to pay political dividends in American political life. It’s relatively easy to try to scare up votes based on fear mongering and vilifying people. It’s harder to have moral scruples and engage with the complexity of policy and politics in the wider region. The easy solution is to try to scare the hell out of the electorate. Politicians have done that forever and will continue to do it and we’re obviously seeing them do it at a level now that really is on a different scale.

What do you make of President Biden and the Democrats’ willingness to embrace tougher stances on immigration and even mayors like Eric Adams in New York City decrying a migrant crisis?

On the whole, the conversation for the last three years has increasingly drifted right. That was the case even before Texas Gov. Greg Abbott started busing migrants to blue cities. Part of the reason for that is the Trump administration really broke the system and they did it deliberately. Picking up the pieces is an incredibly complicated undertaking for any government, under any circumstances—but especially one that’s dealing with a country that’s as divided as the United States is now, and a government that had to deal with a moment of unprecedented mass migration in the world and in the hemisphere the likes of which we haven’t seen in decades.

I do feel some sympathy for the Biden administration in the sense that their backs really were up against the wall when they took office. There was a risk aversion in the upper reaches of the White House from engaging directly with this issue because there was a feeling—I don’t think they were wrong to feel this way—that this issue is just so bruising politically, it’s so hard to come out on top of an issue like this, everyone’s going to be incensed, you’re going to piss off every element of your own constituency, and the other side is going to be attacking you relentlessly. But one of the results of that was that the Biden administration rhetorically ceded a lot of ground to the other side. I don’t think that’s just symbolic. I think the consequences of that start to accrue and have very concrete and physical manifestations.

In the past, the idea that a government, whether a conservative Republican one or a liberal Democratic one, would entertain simply suspending asylum altogether, would have been unfathomable—even when there were acute crises at the southern border. Now, that gets normalized.

On top of that, we begin to see all of these global factors colliding with a real kind of deep cynicism and almost nihilism on the Republican side, where they’re deliberately trying to make the situation worse because it helps them in the 2024 election. I think the political pressure the Biden administration is under is real. And it’s very striking to see them use language from the other side to essentially say: We’re the tougher party now, the Republicans are the chaotic party. It’s incredible to see that leap from someone who had in 2020 campaigned on the very opposite of all of that. But the politics of this are ugly and the Democrats have to come up with some way of fighting through the politics because otherwise they are just going to get obliterated.

In the book you also write that a White House official told you that immigration had become a “democracy issue.” What does that mean?

We’re seeing this worldwide, but especially here in the United States: This is a moment of the rise of populist authoritarianism and it’s, frankly, terrifying. A big part of the appeal of populist authoritarians with the broader electorate is based on people’s confused perceptions of the immigration situation. Insofar as Donald Trump can be said to be saying anything coherent at any point, the one thing that he says consistently, and it has obviously worked for him with a large share of the electorate, is this idea that our borders are being overrun, the demographics of our country are changing, we are being overtaken by a foreign population.

These are all obviously menacing, bewildering things to say and shot through with lies and falsehoods. But that taps into a real fear and confusion in the electorate that will have consequences for the outcome of our elections. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that immigration has the potential to be this powder keg in our politics that can really threaten the institutions that govern civic and political life.

The politics are so upsetting. The human suffering is extreme. The policy solutions seem so far off. It’s easy to get down on all of this. I’m totally sober-minded about the situation we face. But I also hope that one thing that comes through in this book is that the people in it, even when they’ve suffered horrible injustices, are not embittered by that and they’re not defined by that. On the human level, people remain: resilient, ingenious, generous, thoughtful, ironic, funny, and full of emotion. Even as you have these people who kind of get buffeted by all of these historical forces—they still were themselves, they still defined themselves on their own terms.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.