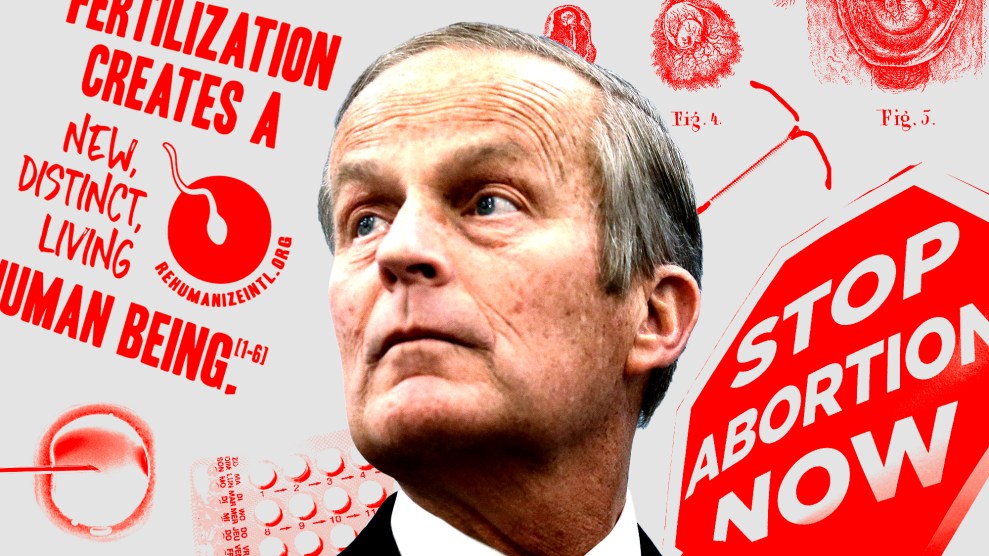

Mother Jones; Charlie Riedel/AP; Unsplash

A few months before the 2012 elections, Todd Akin, the Republicans’ Senate candidate in Missouri, sent his party scrambling when he explained his opposition to abortion even in cases of rape with a now infamous line: “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down.”

Republicans rushed to distance themselves from a comment that ultimately represented Akin’s political suicide. Amid the firestorm, the National Republican Senatorial Committee temporarily withdrew their support, and presidential nominee Mitt Romney immediately clarified that his “administration would not oppose abortion in instances of rape.”

I was reminded of Akin last week when Republican-appointed justices on the Alabama Supreme Court similarly sent the party into a disarrayed retreat, this time over in vitro fertilization. The judges ruled that embryos are “extrauterine children” protected by state law. As a result, multiple IVF clinics in Alabama suspended services. But IVF and its ability to help families have children are immensely popular. To stem the political consequences, the NRSC urged its candidates to loudly back access to IVF. Similarly, Donald Trump quickly announced his support.

While the broader Republican Party faced some struggles in 2012 over its attacks on reproductive freedom—beyond Akin, Indiana Senate hopeful Richard Mourdock, who similarly wanted rape victims to give birth, lost his race—other evidence suggests a modest effect. Despite all the talk about abortion and contraception that election cycle, surveys showed the economy, not abortion, was top of mind when voters headed to the polls. Nor did the gender gap grow in that year’s presidential vote. While its hard to know exactly what voters were thinking, they were making choices with the knowledge that Roe v. Wade protected them from the GOP’s anti-abortion, anti-contraception agenda.

This year, reproductive rights will again be a prominent part of the election conversation, but without Roe, the debate is far less hypothetical. As Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, puts it, reproductive rights will be completely “front and center” in 2024. And as opposed to 2012 when “everyone told women, ‘Don’t be silly, this will never happen,’” she says, in a post-Dobbs world, a broad rollback of reproductive healthcare can happen, and is happening.

Republican rhetoric from a dozen years ago has transformed into a workable legal and legislative roadmap. And while Akin’s comments were extreme, they were not an aberration: as a congressman, Akin had signed onto a 2011 bill backed by a majority of the Republican caucus that would have rewritten the definition of rape and limited federal abortion funding to a narrower range of victims. That followed the party’s attempts to block an Obama administration mandate that insurers cover contraception. Presidential candidate Rick Santorum, who won the first in the nation Iowa caucus that year, argued states should be able to ban contraception. Romney ran on defunding Planned Parenthood.

Twelve years ago, Akin and his allies couldn’t actually enact this agenda, including laws that would have forced rape victims to give birth. But today, states have banned abortion in cases of rape. Even where abortion bans technically have a rape exception, it’s proven virtually impossible for assault survivors to access an abortion. As a result, research suggests that thousands of adults and children who are raped are giving birth against their will. Iowa has stopped paying for emergency contraceptives for victims of sexual assault. In 2012, Mourdock said that if a woman gets pregnant from rape “that’s something God intended.” This month, Alabama’s GOP-appointed chief justice wrote that destroying an embryo would incur “the wrath of a holy God.”

In 2012, Santorum ran on the idea that not only Roe v. Wade, but Griswold v. Connecticut—the landmark Supreme Court case that created a right to contraception—had been wrongly decided, and that states should be allowed to ban birth control. Now, the Supreme Court has overturned Roe and several justices have signaled that Griswold may fall. In 2022, nearly every House Republican opposed legislation to protect contraception access. A new poll from Americans for Contraception found most Americans believe access to contraception is at risk, with 80 percent—including 72 percent of Republicans—saying preserving access is “deeply important.”

During his White House campaign, Romney rebuffed the idea that a state would try to ban contraception: “I don’t know whether a state has a right to ban contraception. No state wants to.” Of course, at the time, it was clear that states did not have the right to ban contraception. But 12 years on, the truth is murkier. Without Roe, many GOP-controlled states are moving toward policies of fetal personhood, just as Alabama now considers embryos to be children. And this principle is being used to take aim not only at IVF, but also at emergency contraception and IUDs, which the anti-abortion movement claims are abortifacients: A new bill proposed in Oklahoma explicitly bans EC, and in Indiana, a bill to provide access to contraception excludes IUDs on the false premise that they cause abortions. Even the iconic and widely prescribed pill is a target. After Elon Musk posted on X this month that hormonal birth control “makes you fat, doubles risk of depression & triples risk of suicide,” a GOP Michigan lawmaker responded that it should be banned. Last year, the conservative Heritage Foundation tweeted that the Republican Party should return the “consequentiality to sex,” with a goal of “ending recreational sex” by stopping the “senseless use of birth control pills.”

In 2012, it was the idea of fetal personhood embedded in Akin’s worldview that frightened voters. But in 2024, the fear comes from real-world ramifications of fetal personhood that are harming actual people. Alabamans have had their IVF treatments cancelled, and Republican Gov. Greg Abbott recently admitted to a CNN interviewer that Texans pursuing IVF might soon be in the same boat: “You raise fine questions that are complex, that I simply don’t know the answer to.” Indeed, last year, a lawyer currently employed by Trump, Jonathan Mitchell, filed a wrongful death suit in a Texas state court over an abortion—the same kind of case that led to Alabama’s new IVF ban.

In overturning Roe, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that he was returning the issue of abortion to the states. But Republicans in Washington—not to mention anti-abortion rights legal advocates—have national ambitions. Republicans in Congress have introduced the Life at Conception Act which, as the title suggests, defines life as beginning at conception. Trump has reportedly expressed support for a national abortion ban starting at 16 weeks. This month, the Supreme Court will consider whether to ban medication abortion, the most common form of abortion and the one used during the first trimester, nationwide.

The 2012 election was more than just a prelude to today’s political reality; it can serve as a reminder that the current reality was always part of the plan.