This essay was originally published on Dashka Slater’s Substack, A Sigh of Relief, which you can sign up for here.

I was homeless when I started college at the University of California, Berkeley. First-year students weren’t guaranteed housing in those days, and I’d been unable to secure a spot in either the dorms or the student-run housing co-ops. Over the summer, I’d applied for rooms in dozens of shared houses and apartments listed at the University Housing Office, but nobody wanted to rent a room to a 17-year-old freshman. And so, as my first day of college approached, I was couch-surfing, spreading out my sleeping bag in the living rooms of the daughters of my mom’s friends and acquaintances, most of them much older than me and visibly unenthusiastic about my presence.

Finally, I was desperate enough to respond to an ad for a room that had been posed on the bulletin board of one of Berkeley’s co-op supermarkets. The room, in a rambling wood-shingled North Berkeley house, was lovely, but it came with a catch. The residents were the remaining members of a 1960s commune that had dwindled nearly to extinction. I would only be allowed to stay if I eventually agreed to join a “group marriage” with people several decades older than me.

Yes, that means exactly what you think it does.

I successfully dodged this commitment for a couple of months, dutifully appearing for the occasional communal dinners but skedaddling as soon as I’d cleared my plate. But my lack of interest in even talking to the other people in the commune, much less, er, marrying them, didn’t go unnoticed. At the beginning of November, I came home from school to find a note taped to my door telling me I needed to move out. In what felt like a miracle, the same day I was kicked out of the commune, I finally landed a spot in a student co-op.

It is for this reason, perhaps, that I’ve followed UC Berkeley’s 55-year quest to build student housing on the site of People’s Park with particular interest. To this day, 10 percent of Cal students are homeless, with the university providing housing for only 23 percent. Yet despite my firsthand experience of the housing crisis, as a student I dutifully adopted the position of my fellow campus leftists: People’s Park was a sacred site, an ecotopian symbol, a legacy of student activism that must continue in its current state for evermore.

Ken Swofford, 69, rested by his tent at People’s Park, where the University of California is determined to build housing for 1,100 students and 100 unhoused and low-income people.

Eric Risberg/AP

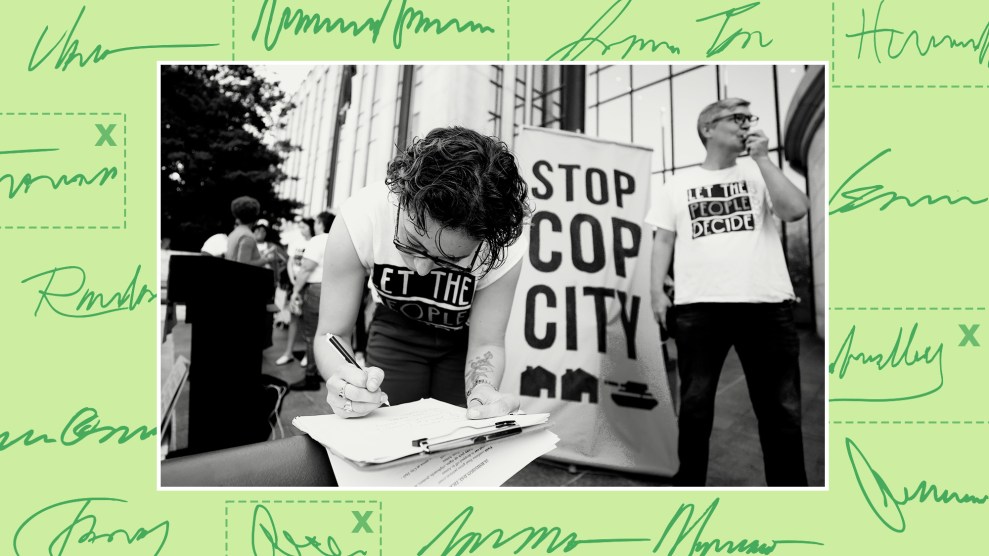

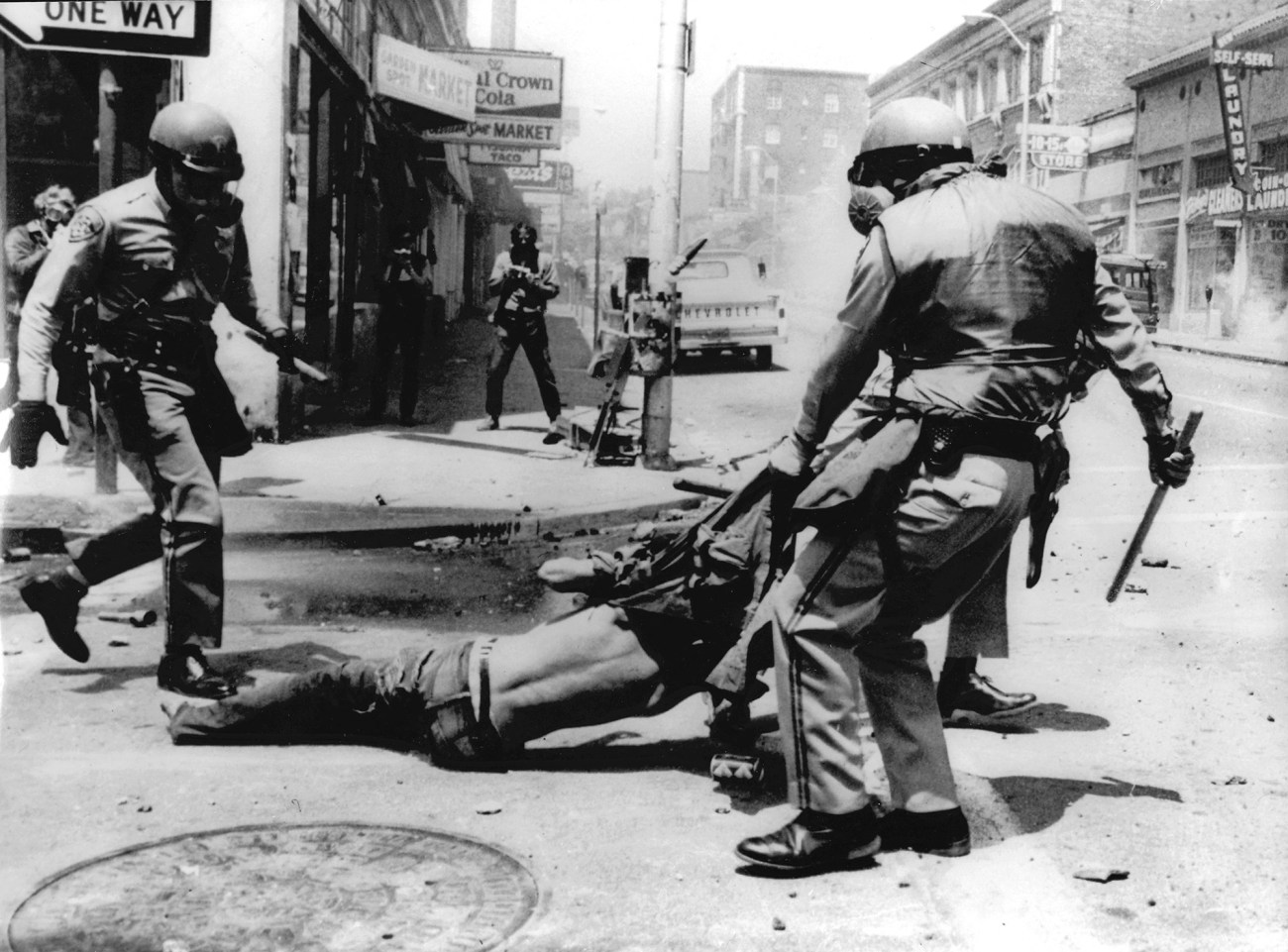

The story of People’s Park started in 1969. The university had razed the homes on the 2.8-acre property years before with the intention of using the land for student housing, but then had left it as a vacant eyesore. When students and local residents decided to turn the lot into a kind of community garden, the university responded by fencing it off. On May 15, inspired by student body president-elect Dan Siegel, who urged the crowd to “go down and take the park,” 3,000 protesters marched toward the park. Law enforcement turned out en masse to stop them. As the Bancroft Library writes:

The confrontation quickly turned violent with demonstrators throwing bottles and rocks, setting cars alight, and smashing fire hydrants open. Law enforcement first responded with tear gas, and then with shotguns loaded with rock salt, birdshot, and buckshot.

Police arrest a student during unrest that followed the closure of “People’s Park” in June 1969.

AFP/Getty

In the ensuing riot, a bystander, James Rector, was killed by police, another was blinded, and many more were wounded. Gov. Ronald Reagan declared a “state of extreme emergency” and dispatched 2,700 members of the National Guard to enforce a curfew and a ban on public gatherings.

And thus, a symbol was born.

“The Park is a symbol to those who support it of freedom and the struggle for freedom…To some, the Park is an eyesore to the community. To others, it is an oasis where one can freely express themselves,” park activist Ron Jacobs wrote in 1981.

I was a student around the same time those words were written, and my job as a lobbyist for the leftist student government required me to pretend that I saw People’s Park as Jacobs described it—as a holy space, a symbol of Freedom and Community and Sticking It To The Man.

In reality, what I saw at People’s Park were fights, drug use, dog and human shit, and people who were either drunk, high, experiencing a psychotic episode, or some combination of the three. At night, I avoided walking anywhere near it, for the same reasons I avoided any place with an abundance of unlit greenery and groups of inebriated men.

But even as the park itself deteriorated, the story of the park flourished. During the 1990s, I covered the battles over the park as a reporter, once spending an entire weekend at a kind of collective therapy session for activists, residents, and police who had participated in the ritualized battles over the park for decades. Those battles only served to cement People’s Park as a place where symbolism existed independently of experience, sometimes with tragic results.

As the Los Angeles Times recalled recently:

In the early 1990s, a machete-wielding activist infuriated by the university’s construction of volleyball courts at the park was shot and killed by police after she broke into the campus residence of then-Chancellor Chang-Lin Tien. Police said they found a note in the teenager’s bag. It read: “We are willing to die for this piece of land. Are you?”

And so it has continued up until the present moment. “It’s not the land only, it’s the history. You are taking part of Berkeley history,” a demonstrator explained last month during yet another round of pro-park protests.

But by then, the gulf between symbol and reality had become impossible to bridge. In early January, the university made a surprise attack during the dead of night and quickly erected a double-high wall of shipping containers around the park’s periphery before bulldozing the lot completely. There was literally no land left to defend. Only the history. The symbol.

Workers erect a wall of shipping containers around People’s Park on January 4, 2024. (Brontë Wittpenn/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Still, the story wasn’t finished. Earlier this month, the dispute went before the California Supreme Court. Two community groups—Make UC A Good Neighbor and The People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group—had sued the university to block its plans to build housing for some 1,100 students and 100-plus formerly unhoused and very-low-income people, while keeping 60 percent of the lot as publicly accessible open space and erecting a memorial to commemorate the park’s history. The groups argued that the university should have assessed the noise the students would generate and considered alternative sites.

These arguments, which prevailed in a lower court, seem unlikely to stop the project now—not since last year, when the state legislature preemptively passed a state law saying universities don’t have to do either of the above when building student housing.

What’s interesting to me, at this point, is why some of the campus radicals I went to college with are still fighting this fight. Surely advocates for the homeless must see that housing 1,200 people will do more to address local homelessness than allowing a couple dozen people to camp in the park. And if they don’t see that, why not?

In January, four of the founders of People’s Park wrote in The Nation that the park has spent the past 50 years as “a site of the unhoused, the deranged, and the forlorn.” But they were still not willing to consider the park a failure.

“People’s Park, at its best, was an expression of the utopian yearnings of a generation that sought to make a better world,” they wrote, arguing that if only the university had acted differently, it would have lived up to those ambitions.

A drone view of the stage at Peoples Park.

Jane Tyska/Digital First Media/East Bay Times/Getty

In my mind, at least, People’s Park is an expression of something else entirely. Rather than utopian yearnings, it represents the way symbols can be separated from their actual significance. No matter how beautiful the dream of People’s Park was, the reality was quite different—and has been for decades. Yet the discourse remains unchanged and untouched year after year. This is what symbols do. They can persist long after their meaning has left the building. Just ask The Cross.

It happens with astonishing regularity. Think of all the times when an individual offender has been used to symbolize Crime Writ Large, as when Richard Allen Davis, who killed 12-year-old Polly Klaas in the early 1990s, was used by California politicians to pass the horrific three strikes law that drastically increased the amount of time people served in prison. (About one-third of California prisoners today are serving sentences extended by that law.) And consider how historical figures have become stand-ins for political ideals, and how wounded we often feel when we learn of their flaws. Does Thomas Jefferson embody America’s virtues or its vices? What about Abraham Lincoln? John Muir?

Consider how the right has used trans kids as symbols of the Breakdown of Society, or all the political mileage both the left and the right can get by simply mentioning the acronym DEI. Think about the way US realtors responded to the “racial reckoning” of 2020 by removing the phrase “Master Bedroom” from its lexicon, rather than actually tackling housing discrimination and predatory lending. Guns, flags, cars, abortion, marriage, Israel, Palestine—when a word alone is enough to conjure an entire political discourse, you know that the stark simplicity of the symbol has eclipsed the messy complexity of reality.

We are, by nature, symbolic thinkers. It’s part of what makes us human. But symbols are there to represent abstractions, not to replace them. Too often, we waste our time arguing about the symbols themselves, rather than working for the ideals they’re supposed to represent. Real change can only happen when we see things as they are—complicated, concrete, and contradictory.

Was People’s Park a glorious triumph or an abysmal failure? In symbolic terms, it must be one or the other. Only when we remove the weight of symbolism can we see it as it really was: a little of both, and a lot of neither.