Frustrated by the two-party system? Polling shows you’re not alone, with more Americans than ever supporting the idea of a third party. But the winner of November’s presidential election will be either Biden or Trump, and voters weighing other candidates need to consider if a protest vote to end the duopoly might instead help end our democracy. In the May+June 2024 issue, we examine the past and present of third-party outsiders, and how they could upend this year’s race. You can read all the pieces here.

In 1990, frustrated with our democracy, Ralph Nader wrote an article for Mother Jones about the obvious need for a “new politics.” The crusading consumer advocate, famous enough to have hosted Saturday Night Live, warned that “growing poverty” and “bureaucratic rigidity” were among a “litany” of issues plaguing America. But, more than any specific policy, Nader bemoaned a system—full of broken institutions and entrenched powerbrokers—that silenced common people’s demands for a better nation. Still, Nader saw some hope in the decade to come: “The nineties promise to be a time of pent-up consumer and citizen frustration,” Nader wrote, “[that] if joined to a new, modernized assortment of political tools, could fuel a new political movement for a real democracy.”

More than 30 years later, the 90-year-old Nader is still waiting—frustrated, and occasionally incredulous—for a revolution that never arrived. The 1990s did not give America Nader’s longed-for mass movement. In fact, something like the opposite occurred. Bill Clinton’s so-called New Democrats shifted the party rightward, upending Nader’s vision of New Deal, populist engagement.

“Go back to the Mother Jones articles,” Nader said earlier this year, when I called to discuss third-party politics in the 2024 election, referencing the series of columns he wrote in 1990 for this magazine. Everything he wrote back then, Nader explained on the phone, still needs to happen.

For years, Nader was a respectable rapscallion of the Beltway. He rose to fame in 1965, with his book attacking General Motors, Unsafe at Any Speed. The young, telegenic lawyer identified horrific safety inadequacies in the corporate behemoth’s cars, especially “the sporty Corvair.” In retaliation, General Motors executives hired a law firm that, in turn, hired a former FBI agent who spied on Nader. “Our job,” his antagonists wrote in a letter at the time, is to look into Nader’s “friends, his women, boys, etc., drinking, dope, jobs, in fact, all facets of his life.” After the spying came to light, the appalling tactics used against him propelled Nader to further fame, which he then leveraged to spur congressional action. It worked. In 1966, Congress passed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act.

In 1974, Ralph Nader at a press conference accused President Richard Nixon of giving in to the “most outrageous and extreme” demands of big business.

Bob Child/AP

This accomplishment became a model for Nader’s future work: Find a problem, expose it in the press, use media pressure to bring about congressional hearings, and then push for specific legislation. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Nader and his famous “Raiders”—a group of dorky college kids and young lawyers who wrote book-length policy briefings—created a brand of consumer politics with clear policy outcomes: new regulations, new laws, even some new agencies. Nader’s theory of change offered a palatable radicalism. Here was a tie-wearing wonk yelling about adjusting policy, unlike the long-haired hippies who had demanded revolution. His efforts resulted in the creation of some pillars of the regulatory state: the Occupational Safety and Health Act, the Freedom of Information Act, and the Consumer Product Safety Act, among others. Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. famously groused in a 1971 memo to the Chamber of Commerce that Nader’s PR campaign had made him “perhaps the single most effective antagonist of American business.”

But in the 1980s Ronald Reagan’s rise in Washington was tantamount to a backlash against Nader’s leftist visions. “At the same time, Congress began to weary of someone many members saw as an annoying Old Testament prophet,” Mark Green, who was often a co-writer with Nader, explained in the Nation. “And the media, too, moved on.”

Marginalized, Nader, who had famously not run for office, instead positioning himself as a citizen activist, finally lowered himself to electoral politics. In 1992, he launched a write-in campaign in both of the New Hampshire presidential primaries calling for Republicans and Democrats to vote for “none of the above.” “The only way people will get their attention,” Nader told the press, warning of complacent politicians, “is to write in my name.” (He won about 1 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary.)

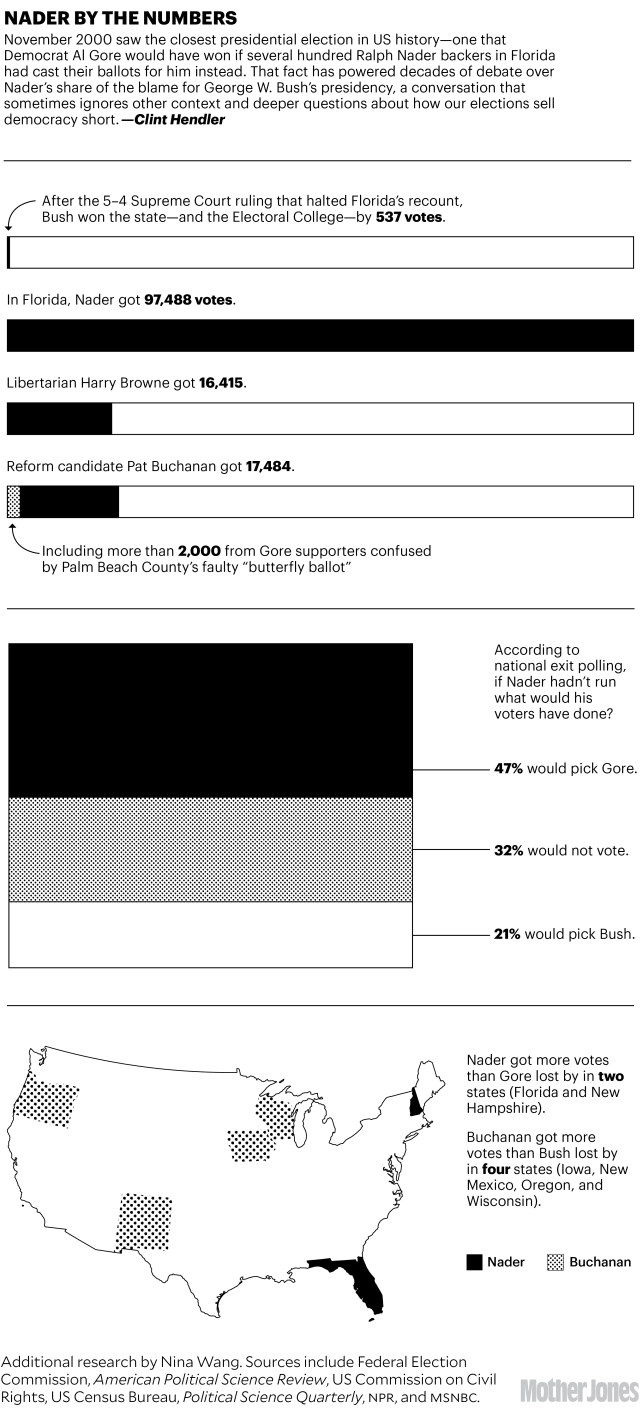

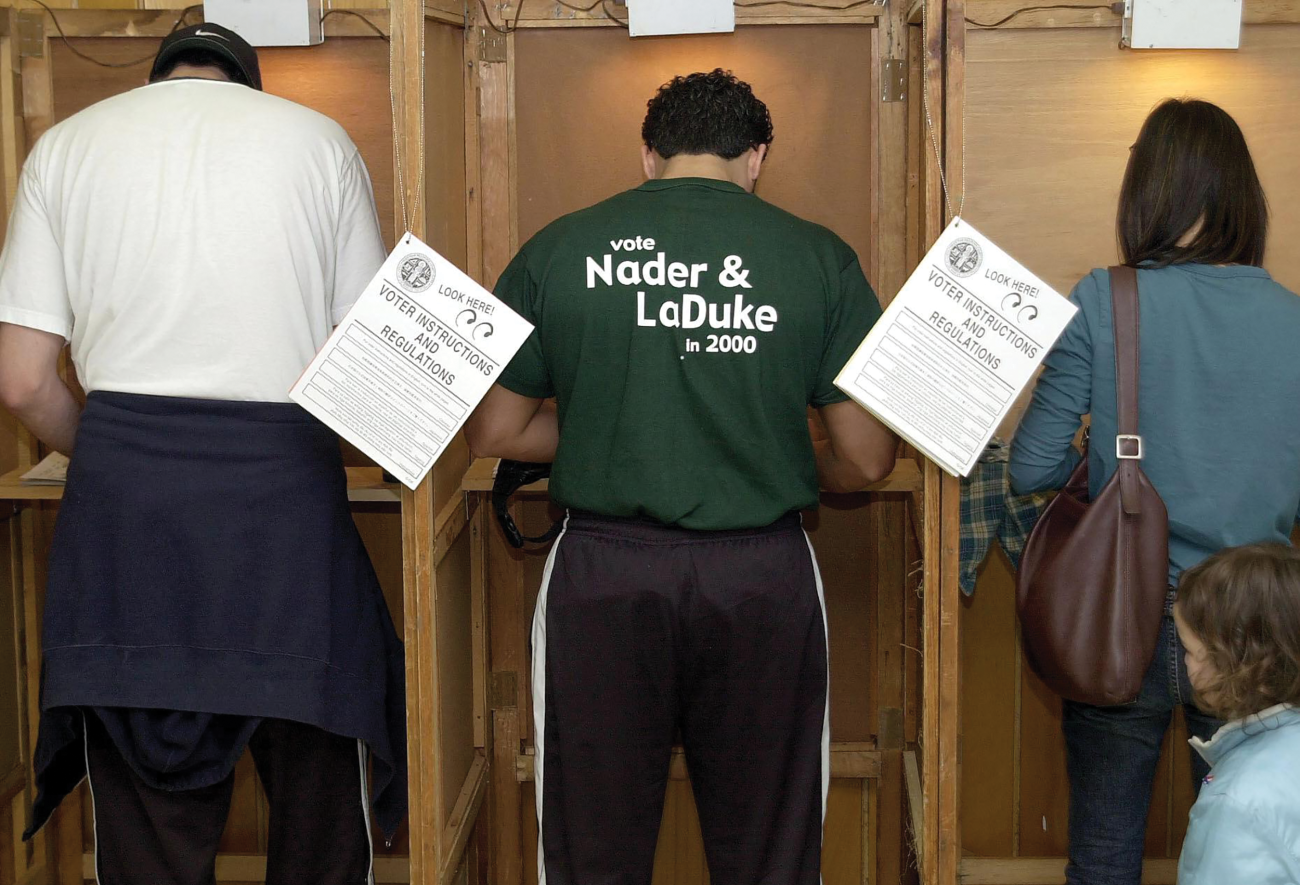

In 1996, Nader again ran a half-hearted presidential campaign, loosely affiliated with the Green Party (he did not accept its platform but in some states ran on the Green ticket). And then in 2000, Nader went all in campaigning for the presidency in 50 states. The 97,488 votes he won in Florida would become a constant talking point—and, in his mind a stalking horse—in the debate over why Al Gore lost to George W. Bush. Since then, Nader has fought the label of the “spoiler” who—as columnist Jonathan Chait notably argued—put George W. Bush in the White House by siphoning votes from Gore. Nader has been adamant that suggesting that his run resulted in Al Gore’s loss is ridiculous.

In recent years, Nader launched a print publication, the Capitol Hill Citizen. (“Online is a gulag of clutter, diversion, ads, intrusions, and excess abundance,” he explained to Politico.) And he has continued to do what he has for much of his adult life: Bug reporters and tell them to stop trying to win awards and start covering committee hearings.

I called the former presidential candidate and former Mother Jones contributor to talk about how he views the potential of third-party politics, the problem of the “lesser of two evils” arguments, and the media’s failures—including mine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there an exact moment when you decided that you would run for president in a serious way?

It became more and more difficult to get anything done in Washington. When Tony Coelho (D-Calif.) was head of the House Democratic reelection committee [in the early 1980s], he persuaded the party to go big for corporate PACs, to go to the receptions around Capitol Hill—and started to quid pro quo. He said we can raise as much money as the Republicans, what are we waiting for?

And you can see the decline in congressional hearings. They won fewer elections. Regulatory agencies didn’t respond to our petitions for health safety standards. It was declining everywhere.

So year after year, you start asking yourself: What do you do when you get up in the morning? You can’t get hearings anymore. It’s getting harder to get through to members of Congress. The press doesn’t pay any attention. If you don’t get press, the members of Congress don’t pay attention. It becomes a vicious circle.

Hey—you gotta go into the political arena.

But we have a two-party duopoly that has huge fences around itself, erected by the corporate-conflicted political and media consultants—which the progressive press has ignored enormously in recent years and who have taken over the Democratic Party. The idea behind third parties in the 19th century was you push one of the two parties—or maybe both parties—and they eventually adopt what you’re pushing. And I learned that wasn’t possible. The Democrats would respond not by moving in the direction of working for the people. They responded by scapegoating their losses onto the Green Party.

They’re great scapegoaters—they never look at themselves in the mirror.

You ran in every presidential election from 1992 until 2008. When did you realize that your path in electoral politics would lead to scapegoating?

When the media blacked us out. Most people who knew my name as a consumer advocate didn’t even know I was running. It’s an impossible task. You can’t do it. It’s a two-party dictatorship. The media is heavily to blame for this, including the progressive media. They keep toting the Democratic Party line: They’re not as bad as the Republicans. Which is true. They’re not as bad as Republicans.

But they’re both very bad—by any level of reasonable civic expectation.

As you look back on the progressive “lesser of two evils” argument, it seems this is always the way the press frames third-party politics. What is the problem with that?

[This argument] doesn’t start with the progressive agenda and empowering the people. It starts with which one is worse: Democrat or Republican? It doesn’t start early enough and fundamentally enough, and that’s the reason why the progressive press fell prey to the “anybody-but-the-GOP” and made no demands on the Democrats. Like the labor unions, they endorse early, and they make no demands. Labor unions just endorsed Biden weeks ago—with no demands to repeal Taft-Hartley, no demands for $15 or $20 minimum wage, no demands for anything. They just went, hey, this is not the time. I love that phrase. “This is not the time.” If you go lesser-of-two-evils every four years, you’re gonna go lower. A liberal Republican from the 1970s now would be considered a progressive Democrat. That’s how far the Republicans have gone.

Then the other thing that is even more disgraceful is they attack people like me. You know, the Nation attacked me. They attack people like me for carrying their progressive agenda. They’re panicking. They don’t even know how to hold out until a few days before the election to maximize their bargaining power.

It’s amazing to watch the toadiness, the civility, the peonage. They’re not even demanding scraps on the table—not even demanding scraps.

In 2024, we’re looking at a race in which we have two deeply unpopular candidates, and there is no real infrastructure for third-party politics. Was the third-party option kneecapped or were you unable to build it during your runs?

Now you’re onto something very important. That’s the problem. The Green Party doesn’t run enough local candidates. You can’t have a national campaign without local candidates. They have about 250 local candidates, usually every four years, out of thousands of opportunities—you know, Zoning Commission, City Council, Board of Education. They’re not serious. They just love to have their beliefs reaffirmed by whoever’s on the stage and rah-rah them. They’re not poor. They’re middle to upper-middle class. But they don’t raise enough money for full-time organizers in the field. The people who shout the most are the people who do the least work. Their main function is as scapegoats for the Democrats. Imagine the Democrats saying that Dr. Jill Stein cost Hillary the election. [Laughs.] It’s a joke. They don’t know anything about regression analysis, or a billion dollars of stupid ads, repeating ad infinitum: Donald Trump’s not fit to be president, Donald Trump’s not fit to be president. There was no ground game in Pennsylvania and Ohio. And that’s the problem. They’re prisoners of the political media consulting firms.

Don’t get me started.

But if the point of a third-party campaign is to push, and you are saying that third parties failed to help you do that, do you feel like you were able to push in your campaigns?

No, I wasn’t able at all. I went to scores of fundraisers. I went to 50 states. I put on my stage people running for the Senate for the first time like Medea Benjamin. I did the whole nine yards. It didn’t matter.

It seems as if you’ve been defeated by the inadequacy of third-party politics, and yet also need to defend them. And it reminds me of some of your writing, including for us in the 1990s, about creating the tools for democracy and citizen activism. What is your assessment of the current state of democracy?

Did you read the book Crashing the Party?

I did.

Well, I’m being redundant, then. The problem with these third parties, compared to those in the 19th century, is they don’t come from the people. You make a list of all the Green parties—the so-called activists—all of them have health insurance. I hardly met anybody who didn’t have a good job, or a good retirement, or health insurance. What’s not to like? They’re not hurting. In the old days, they came out of being pummelled into poverty by the railroads and the banks. And then there were the Eugene Debs supporters. That’s a way to build the third party.

Green Party presidential candidate Ralph Nader answers questions from reporters after speaking at a rally on universal health care.

Matt Moyer/Sygma/Getty

The modern third parties get hit with “spoilers” by their friends: “Hey, you’re supporting a spoiler. Do you want another GOP president like Bush?”

What are we spoiling? We’re trying to go after a system that’s spoiled to the core. You’re calling me a spoiler? What am I doing to spoil anything? Other than exercising my First Amendment rights of speech, assembly, and petition to try to advance majoritarian agendas—many of them supported by 70 to 80 percent of the American people, including a lot of conservatives. They don’t even know how to argue the case. And don’t get me started on foreign and military policy. Where they’re clueless or they’re not interested at all in the empire, or the military budget, or the slaughter of people, of civilians everywhere: Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, Palestine. It’s disgraceful.

You’ve said “spoiled to the core” for years now. So if it’s spoiled to the core and the third parties haven’t been working to change that, I’m still confused as to why you remain such an advocate for them.

I’m looking for a different third party—like the one Tony Mazzocchi, the greatest labor leader of our generation—envisioned. He came out of Long Island—and during World War II he helped liberate the death camps. He comes back. He starts a union in a largely female factory. Then he goes into the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, and he gets them to oppose nuclear power—even though they have workers in nuclear power. He comes down [to Washington, DC,] and works with me to get OSHA through. He gets scientists to connect with blue-collar workers on toxics in the workplace. He’s everywhere. Then he started a party, but he didn’t want to have candidates. He told me he wasn’t interested in a 1 percent party. He said organize until you float a party where you can start getting 10 percent, 15 percent. But he never reached that because the unions he talked to were part of the Democratic surrender core. They couldn’t out-argue him. Nobody out-argued Tony.

I want to ask about 2024. It seems that the rhetoric of the “lesser of two evils” is especially heightened—

Wait a minute. It’s the wrong question. It’s the wrong question. The first question is: Why isn’t the Democratic Party and Biden 20 points ahead of a chronic liar, thief, crook, narcissist, smearer, slanderer, ignorant, stupid Trump and his followers? That’s the question. You don’t take the dereliction of the party knuckling under their corporate political media people and start there. You start with: Why aren’t they landsliding him? Do you know about the effort with Mark Green and me in 2022?

I don’t. Tell me—

You know anything about WinningAmerica.net?

I don’t.

See, Jacob, no matter where you went, where you worked—Arkansas, everywhere—you’re part of the problem.

I’m sure I am.

Get on the computer right now—go to WinningAmerica.net. On July 23, 2022, we offered the Democrats a huge presentation—six and a half hours and only a handful showed up. We had 24 civic leaders. And the sons of bitches didn’t even pick it up. Even though it was nominally endorsed by Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.), Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.), and Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.). But you couldn’t get the queen, [then–House Speaker Nancy] Pelosi, to even return calls. I knew her when she was 45 years old coming out of San Francisco—didn’t matter. She wouldn’t endorse it.

We put out reports, we put out articles. I’m gonna burn your ear, so be patient with me. The magazines don’t even cover it. So I call the editors of the Nation, Mother Jones, In These Times, Washington Monthly, the Progressive—lucky to even get a callback. I used to write for these publications before the editors were born. But they wouldn’t even call back. You got to start digging deep, Jacob—you got to dig deep into the malaise, the surrender, the low expectation level, the narcissism, the smugness of our side. We ought to be ashamed of ourselves. We have the most powerful arguments in American history, against the worst tyrants and corporate indentured servants in American history.

So why am I talking this way? Because you’re like the 40th progressive reporter I’ve talked to in three years, and they all write the same goddamn stuff: the same stupid, superficial stuff.

What do they write?

Just look at the articles: spoiler, third parties that elected Bush, Stein is a troublemaker—on and on. The party line: Don’t they know this is not the time? It’s critical for democracy. We got to go with the Democrats. They don’t challenge the Electoral College—the Electoral College elected Trump, the Electoral College elected Bush. What are you doing scapegoating me and Stein?

There really is something deeply wrong. The press is part of the problem. You can’t say they’re ignorant. I give them stuff to read. They know what they can read. They come back with the same rubber-stamp articles. The latest one is Michael Scherer in the Washington Post. I must have talked to him for an hour and a half. Look at the stupid article he wrote and look at the even more erroneous headline that he wrote back a few weeks ago. And the guy was White House correspondent.

You had problems with that article?

Yeah, he immediately tried to maneuver me into—after years of opposing the Democrats—saying I’m supporting Biden. Supporting Biden? The guy’s a war criminal on steroids. The guy doesn’t know the meaning of peace negotiations. He doesn’t know the meaning of humanitarian aid. All he knows is shipping cluster bombs to Ukraine and 2,000-pound bombs to the Israeli war machine.

In the article, you mention we are stuck with Biden. But do you really feel that we’re stuck with him?

No, the country’s stuck with Biden. That doesn’t mean I am. I never tell anybody how I vote. It intrudes on my communication, my access to people. They start pigeonholing you, stereotyping you, putting words in your mouth. I say to people: Vote your conscience. I’m a Eugene Debs guy.

If you vote for Biden, he’s never going to look back because he knows you have nowhere to go. If you want to vote for Biden—hold off the vote until the last minute and get some concessions for heaven’s sake.

Well, let’s talk about that. Specifically, what are the concessions right now that you think are most vital that the left should be pushing Biden for?

How much time do you have?

Well, I think you have more hard-out on timing than I do, but I will—

Go to WinningAmerica.net. And look at my presentation. And you’ll see a list so I don’t have to repeat it.

When talking with you and reading about you, it’s clear that access to your message, and your ability to have the power to push, is so mixed with your belief of how to fix what’s wrong. And that has led some to say that your campaigns are egotistical. Do you think the run in 2000 got in the way of your ability to advocate effectively for progressive policies in the past 20 to 30 years?

That’s nothing more than an excuse. Even if I didn’t run, they were going to marginalize me even worse. That’s why I ran, because they were excluding our groups. We couldn’t get our calls returned. I don’t buy that.

After 2000, Biden was on television. He said, “Nader better not come up here anymore.” Can you imagine the arrogance of this guy? This is after Gore could have easily landslided this bumbling governor from Texas, who had a horrible record on children, pollution, poverty, you name it. He’s got the gall to say—and I laughed at the time to my friends. Look at this guy. He’s trying to keep me out of Capitol Hill.

I’m not laughing now. They froze me out of almost every hearing.

You’re connected deeply with consumerism, but that’s not exactly the creed of the left now. Your time charts onto what people would call neoliberalism—beginning under Carter, then growing with Reagan, and flourishing with Clinton. Do you think of yourself as someone who’s critiquing capitalism? Or are you doing something different?

It’s corporate capitalism that I’m against. Not small business, Main Street, mom-and-pop capitalism. And the difference is far more than a difference in magnitude. It’s the difference in the quality of power. There’s no comparison between giant corporations and small businesses. So that’s one. You can’t have a society without markets. The key is to make them local, competitive, accountable, replaceable, accessible, sue-able, and so on. But the big corporations—that’s where progress falls down.

Mother Jones—very good empirically. I mean, they really documented case studies of vicious behavior. But they don’t go to the higher level. The higher level is: What do we do with these big corporations? One is we’ve got to subordinate them constitutionally. So corporations should never have equal rights with real people. Now they’re connecting with AI. You want a deadly cocktail? Connect artificial persons called corporations with AI.

Too many progressive reporters don’t know how to take it to an ideological level. I mean, I hate rigid ideologies. But if you don’t take empirical reality and weave it into public philosophies, you’re just gonna be spinning your wheels, exposing one skirmish after another of corporate crime, and going nowhere.

You think I’m optimistic about this conversation with you, Jacob? You know, I have somebody here, listening to the conversation in a chair in the office. And you know what she’s going to tell me? How do you have the patience to do this—day after day after day—and get the same output?

They don’t dig. What you should do is buy yourself a shovel. And every time you’re gonna do a similar superficial story, you say: I, Jacob Rosenberg, am not going to do the same shit story. Just look at the stuff in your magazines, what they ignore, what they go over. The Democratic Party line: “least worse,” or “this is not the time.”

I really don’t want to have these conversations anymore. Because I can’t get through to people.

I don’t disagree with you. I find it frustrating that a lot of liberal press says “least worse.” But I’m also trying to understand if, when you ran as a third-party candidate, you felt that it was effective in changing the things you care about.

I know what you’re asking. The issue is what kind of third-party movements. It’s not, oh, they don’t work, let’s drop them because they didn’t mobilize, didn’t connect with the people, didn’t sweat, didn’t raise money, didn’t hire organizers. Show me a major movement in America that succeeded without organizers—labor, civil rights environment. So the issue is that third parties are essential for a competitive democracy. You cannot have a democracy without being competitive. In other words, having forces being able to replace the entrenched incumbents.

What do you make of something like No Labels, then, that uses the third-party system but takes a lot a money from rich people?

I mean, they are nothing but an amorphous force to further entrench plutocracy, oligarchy, and imperialism. That’s all. Lieberman. All you got to do is say, what do you think? Joe Lieberman.

I wanted to ask about the third-party candidates who are running this year. What do you think of the Kennedy campaign?

I don’t know where he’s going. The question you always ask of campaigns like that is: How many state ballots are they on? I don’t know how many states he’s on. If he’s on just 10 to 15 states, it’s just a speech effort.

Do you think he’s doing something positive in his campaign?

Yeah, he’s enhancing the potential of their scapegoating. He could take more votes from the Republicans the way he’s talking these days. Who knows where he is? He’s a tragedy, unfortunately.

I know you’re constantly asked if you regret running in 2000. And I’ve read your responses. But it seems clear that after 2000, in an example of what you describe as the scapegoating process, you were locked out of Capitol Hill in a significant way. That seems to have made life very hard for you—

Yeah, but remember, it was declining for everybody—the access.

How do you think about the years since 2000? And more personally, do you feel frustration and regret simply because that the election altered your life and ability to do the work that you’re very passionate about?

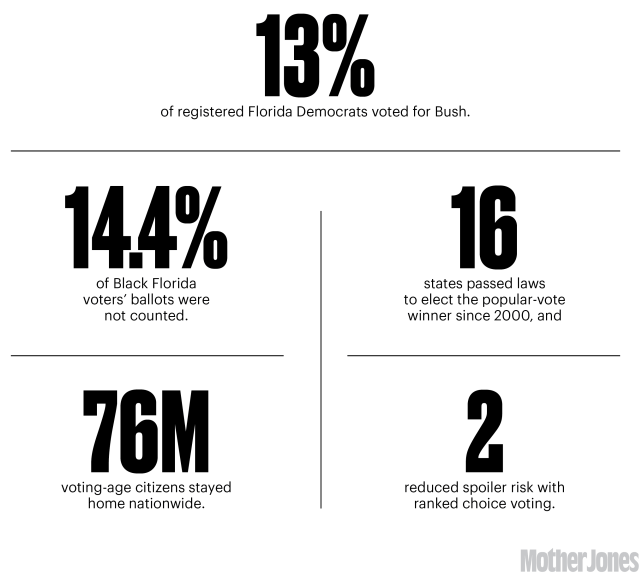

Well, it depends on the object of the regret. What I regret is the 5–4 decision by Scalia. What I regret is 330,000 Democrats who voted for Bush in Florida. What I regret is, you know, the shenanigans with the ballot design, and the hanging chads, which deceived people. And Secretary of State Katherine Harris deliberately allowing a consulting firm to misidentify thousands of people as ex-felons and take away their vote.

Ralph Nader gets a kiss on the cheek from his mother, Rose Nader, following his acceptance speech for the nomination during the Green Party National Nominating Convention in June 2000.

Mark Leffingwell/AFP/Getty

I talked to Gore about 2000. He doesn’t blame the Greens. He said, “Look, we made so many mistakes.” He didn’t get his home state of Tennessee. That alone would have put them in the White House, with everything else remaining the same. He didn’t get Arkansas. That would have put him in. Clinton didn’t help him. One blunder after another—a lot of complacency about how stupid Bush was and that he could never win. They didn’t recognize the winner-take-all Electoral College sufficiently.

However, I’m trying to get the Democratic Party to straighten up. And I’m coming out with a book on this, in June. The Democrats are one of the two 800-pound gorillas. And if they’d open their ears and eyes—WinningAmerica.net redux—it can be repeated two years later, with almost no changes. They could handily beat the Republicans and just be autocrats instead of fascists. How about that for a choice?

That seems like a limited choice.

It’s a very serious choice. [Laughs.]

The Democrats are running on the idea of democracy. What do you think of the Democrats’ version of democracy?

Biden’s running on democracy as he knew it pre-Trump. It’s just revert to pre-Trump days when they didn’t purge and suppress votes, blah, blah, blah. If you do not have the pressure coming from organized, informed people—who summon their senators and representatives and state legislatures to town meetings, who have their own choreography, and they set the agenda—and the legislators, listen to them and hear them and respond and exchange and go back to their jobs instructed, you’re always going to have the few decide for the many, in the interests of the few.

I mean, how many times can I repeat this?