For as long as reality television has existed, so have declarations predicting its swift demise. Cultural prognosticators have said that the genre, something consumed by the idiot masses, is ultimately a fleeting trend.

But after nearly eight decades of enduring such skepticism—yes, it’s been around for that long—reality programming continues to fascinate, repulse, and inform popular discourse. In fact, one could argue that it has survived each death knell with more cultural significance.

I’ve spent my life largely avoiding the genre. That is, until December, when two friends on separate occasions recommended I watch the original The Real Housewives of New York City. I don’t know what convinced me to follow through on the grainy aughts series. But in an instant, I was transfixed, spending the next four months on the pure adrenaline of mainlining all 13 seasons of the original series—before plowing through two other franchises, Salt Lake City and Miami. It was during this madness that I started to dream about Ramona Singer, one of the most offensive yet captivating characters I’ve ever come across on television. (As Hunter Harris remarked in a recent newsletter, the only person remotely like Ramona “lived in the White House and was just found guilty of 34 felony counts.”) I mentally dissected the fallout between Bethenny and Carole. How did this animosity, between two rich white women of middle age, feel at once so alien yet deeply familiar to my own flamed-out relationships of yore? How could I care so intensely? What other sources of pseudo-reality tedium had I been wrongly missing out on? Who created this genius?

This was the background from which I learned that Emily Nussbaum, the Pulitzer Prize–winning New Yorker writer and culture critic juggernaut, was writing a book dedicated to the history of a genre that has since engrossed me. Cue the Sun! The Invention of Reality TV traces the genre’s roots—from the 1940s radio phenomenon Queen for a Day to the ethical ambiguities of Big Brother and beyond—to tell a story that, contrary to its detractors, has earned a serious interrogation.

I caught up with Emily ahead of the book’s release.

Reality TV has forever been dismissed as crude and low-brow. Yet it remains overwhelmingly popular and arguably more powerful than ever before. How have critics written about it in the past—and what did you want to do differently?

One of the main things I wanted to do with Cue the Sun! was not to write about reality TV from a critical perspective, and instead write a nonfiction, reported book. My original idea for it happened in 2003 when I started watching the first season of Big Brother online, which was a truly geeky, weird thing to do at the time. It was around then that I had a conversation with two friends about book ideas, and I said, “Oh, I think there might be a book on reality television.” At the time, it seemed like this big, booming industry. But my friend said to me, “You better write that fast because reality TV is just another flash-in-the-pan trend. It will never last.” Obviously, that was not the case.

Finally writing about reality TV years later, I imagined that the history probably wouldn’t go much further back than the Real World. But one of the first things that I realized looking into the early roots of reality was that it actually started before TV with 1940s radio with what was then called audience participation shows. And at the time, those shows were just as controversial as today’s shows. They inspired just as much moral outrage, disgust, titillation, and high ratings.

This idea today that reality TV is some kind of modern response to technology and narcissism—all that stuff occurred around World War II as well. And that’s part of what the book is meant to do: give the bigger picture of where the genre came from and treat it as something more than just a modern phenomenon.

Until very recently, I had never watched anything on Bravo. I hadn’t even realized that Jeff Probst was still alive and doing Survivor until I came across an article calling for his firing. Which is to say, I’m a relatively new fan of all of this and I want to know where I should start.

You’re not the first person to tell me this. As I talk to more people about reality TV, I’m realizing that people have extremely different relationships with the genre. I recently talked to one teenager who’d never even heard of Survivor, which struck me as a little crazy.

My friend said to me, “You better write that fast because reality TV is just another flash-in-the-pan trend. It will never last.” Obviously, that was not the case.

But the way I define reality TV is taking cinéma vérité documentary, this fancy-schmancy, highbrow art form about observation and patience, and blending in a more commercial, aggressive, fast-moving, pressured format that you can repeat over and over again. Then you merge it with a soap opera. You merge it with a game show. You merge it with a prank show.

That’s so funny about Jeff Probst. So what stopped you from watching reality TV in the past? Did it just seem too crazy?

I’d like to think that I was never a snob about it because that’s embarrassing. But honestly, I’m not sure. I just know that I started watching the Housewives franchise and have been obsessed ever since. I even arranged a dinner at the Regency just to talk about the show with friends and hopefully magically run into Ramona.

I have to say that I was never a Housewives person, and when I first started writing this book, the show was never going to be in it. But it was clear pretty early on that I needed to include it. Though I have to admit that when I watched Vanderpump Rules for my job at The New Yorker, I binged that like crazy. At one point, I was out in LA doing reporting, and I was in an Uber when I suddenly saw SUR, the restaurant from Vanderpump. I was so taken aback, and thought, “Oh wait, I need to go there.” So, I relate to the feeling of wanting to see the people from these shows.

I don’t mention this in the book, but over the years I have randomly run into people from reality TV haphazardly, including, literally, the one person that I have ever been compared to: Irene from The Real World: Seattle.

One of the themes in the book is the shock of reality fame, especially during the first 50 years of the genre. The people who first signed up for these shows really didn’t know what they were signing up for. That’s less true now, not because people aren’t traumatized—I just wrote a piece about Love is Blind, and it’s clear to me that it can still be a very painful experience. But the people who went on the first season of say, The Real World, experienced a kind of fame that almost nobody had experienced before them. The very first people to experience this were the Louds in the 1970s when they were featured in An American Family. They suddenly found themselves becoming household names where everybody felt like they knew them. But they were judged severely.

How should viewers toe the line between that kind of abuse or exploitation and the idea that the people on reality TV shows volunteered for it?

People have always judged people for going on reality TV, from the earliest days when women appeared on Queen for a Day and competed over who had the worst life. Even then, critics were writing, “Who are these narcissists telling their private secrets to the world?” So, there was always judgment for this.

Highly connected to this judgment is the fact that the goal of making shows like this was economic. It was to make content cheaply, non-unionized, without paying writers or actors. There was a simultaneous feeling that reality programming stars weren’t getting paid for this, so people felt like they were asking for whatever abuse may have arisen because they had chosen to do something public. I personally don’t feel that way, which isn’t to say that reality TV participants are saintly. But I do think that people’s contempt for reality TV stars and their acceptance of the exploitation they endure are completely wrong.

I want to add that the crew members for these shows are often also mistreated and a big part of this book is the glimmerings of an attempt to organize crew members and ultimately attempt to talk about reality TV as a workplace. Reality television has always been a strike-breaking mechanism and, as a result, there’s this huge Hollywood culture clash between people who work on scripted and unscripted shows. Some of it is about the resentment that people who work on sitcoms or dramas feel for people who work on reality TV, and the difficulties in sharing solidarity between the two groups.

Strong female viewership, which is key to the genre, seems to be one of the biggest reasons why people feel comfortable condescending to reality TV. What would you say is behind that impulse?

I think that’s definitely true of modern reality TV largely because people associate the genre with Bravo. We see some of that in the early programming days like with Queen for a Day, which was made and run by men but all about women’s lives and made for a female audience, and therefore shared this condescension over what was criticized as female junk shock. But many shows have been broadly adored. For instance, the Chuck Barris shows in the 1970s. Those catered to men, women, and children. Survivor is another blockbuster that everyone watched.

As I point out in the book, there are a lot of ways in which reality shows have used racist, sexist, and homophobic stereotypes as a kind of fuel. They intensify those things. But they’ve also been a platform for representation in incredibly striking ways. I talk a lot about the cast members who were the only Black cast members on large reality casts, which prompted many thoughts about what it means to be in the minority in that way.

There’s also Lance Loud [the eldest son in American Family]. It was such a meaningful thing because they weren’t talking about him being gay. It’s that he was so obviously gay, and everyone could see it. This was shocking and provocative for 1973. It had an enormous impact on people everywhere, including gay men.

When you look at the history of it, there are several prominent gay figures like Richard Hatch from the first season of Survivor. Pedro Zamora, from The Real World, was an incredibly meaningful, heroic symbolic figure, this Cuban American gay man with AIDS who died right after the show was made. While these shows sometimes trade in stereotypes, they also act as pioneering platforms for representation.

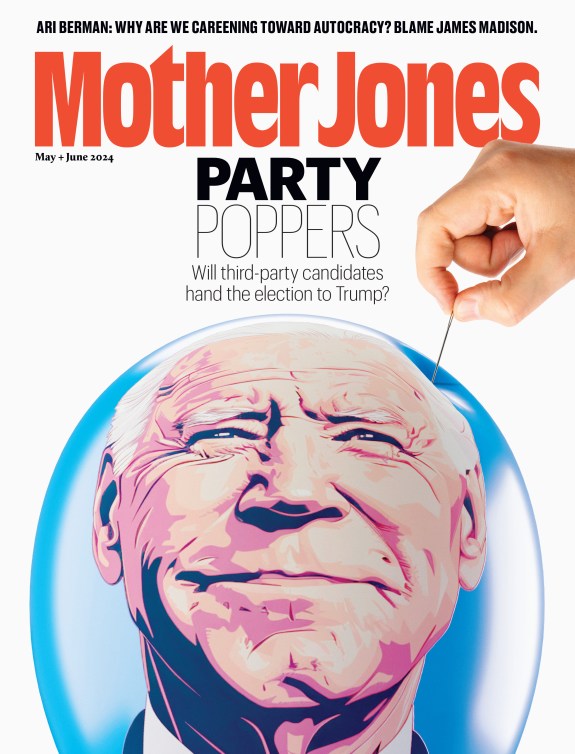

So what about the debate over whether The Apprentice is to blame for the rise of Donald Trump?

There’s no debate whether The Apprentice is to blame for the rise of Donald Trump. Like, I don’t have any question about that.

Well, I wouldn’t say the show is the sole reason, right?

Yeah of course there are multiple reasons. But Donald Trump would not have been president without The Apprentice.

The Apprentice offered a rebranding mechanism that took a failed guy who was bankrupt, a laughing stock who did sitcom cameos in the ’90s, and made him into this incredibly successful businessman that anybody would work for—at least in the eyes of viewers. It’s pretty apparent that a lot of the people who voted for Donald Trump love Donald Trump because they believed he was who he played on The Apprentice.

I’m more interested in the feelings of the people who made the show. The Apprentice was a very well-crafted show made by hardworking people: the producers, the editors, everyone. But I talked to many people on the show who take full responsibility for [Trump’s rise], maybe more than they even should. I would say the lower down on the call sheet they were, the more they recognized The Apprentice was a form of propaganda for Donald Trump. It was a show all about product integration, and he was the main product that it integrated.

The people who take credit or responsibility for—is that said with guilt or in a matter-of-fact way?

Depends on who you’re talking about. Some people do feel guilty about it. Some people understandably say that they never could have known that this would have been the outcome of the show. I talked to many people, and I can’t summarize all of their perspectives because they range. But if you’re asking me: Do I think that Donald Trump was elected because of The Apprentice? I don’t even think it’s a controversy. It’s so apparent—that was a huge hit show.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.