Saul Martinez/The Washington Post/Getty

On December 19, 2023, the vice president’s office quietly launched a new policy initiative. “Kamala Harris will embark on a nationwide reproductive freedoms tour,” read the press release, “to continue fighting back against extremist attacks around the country.”

Harris supporters have worried throughout her time as second-in-command that the Biden administration has saddled her with unwinnable issues, like voting rights and immigration. These were problems with far-off solutions in our current political moment. Abortion, though, is different. Polls, while not always reliable, show that a whopping 89 percent of Democratic women support national laws that guarantee the right to abortion.

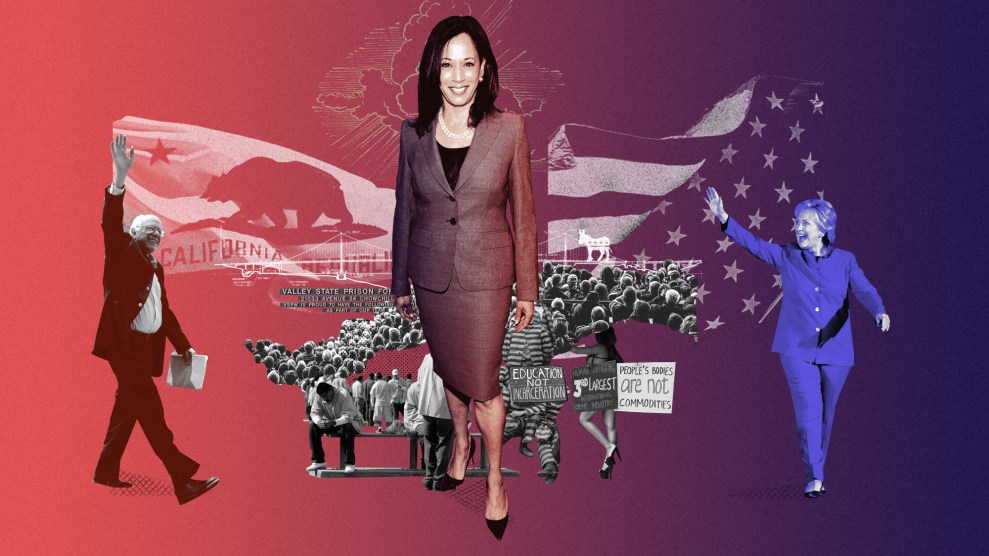

President Joe Biden dropped out of the presidential race on Sunday, throwing his support behind Harris in the effort to beat Donald Trump in November. “I am honored to have the president’s endorsement and it is my intention to earn and win this nomination,” Harris said in a statement, signaling an unprecedented shake-up at next month’s Democratic National Convention.

She’s now tasked with energizing a Democratic ticket that is deeply fractured around a host of issues, including Israel’s war on Gaza. But the party does seem motivated, and unified, by one key plank of the platform: abortion.

Harris’s chance to win might depend on her ability to make voters believe that she is their last chance to save reproductive rights. Former President Donald Trump has already bragged about ending abortion rights and his vice presidential pick, J.D. Vance, has advocated for a national abortion ban.

Biden’s departure from the top of the ticket comes after weeks of maneuvering by Democratic party leaders who expressed deep concerns about Biden’s age and mental acuity. But she’ll still have to prove, amid much doubt, that she is the right person to win in November.

Harris has made a career of firsts under her belt. She’s the eldest of two daughters from a multiracial family; her father, Donald J. Harris, is an economist from Jamaica, and her mother, Shymala, was a cancer researcher from India. Her parents, both activists who met as graduate students at the University of California at Berkeley, divorced when their kids were young, and the girls were raised primarily by their mother in Oakland and, later, Montreal. Her life story is important. And it will be part of the appeal, beyond abortion, as she reintroduces herself to a wider audience.

The Prosecutor

Harris entered public life when she ran for district attorney of San Francisco in 2003. She came to the job as a longtime prosecutor across the Bay in Alameda, where she prosecuted sex crimes. She positioned herself as “smart on crime,” a nod to the “tough on crime” era of 1980s and 1990s policing, but remixed slightly with analytics.

Instead of locking up non-violent first-time drug offenders, her office encouraged them to plead guilty to a felony that might later be expunged if they completed 18 months of job training, therapy, and an internship with a willing nonprofit. She surrounded herself with advocates, forcing her to build inroads with Black and Latino communities that were often at odds with law enforcement.

One of her most memorable moments as DA came early on in her tenure, when she declined to pursue the death penalty in the case of a man who shot and killed a police officer. Officers turned their backs to her when she spoke at the slain officer’s funeral. Former California Senator Dianne Feinstein even jumped in to criticize Harris publicly. “This is not only the definition of a tragedy,” she told reporters, according to SF Gate, “it’s a special circumstance called for by the death penalty law.”

The Albatross

Harris also established herself as a shrewd mover behind the scenes. She wasn’t afraid to go up to the president of a police union, put her finger in his chest, and demand his support, as Politico reported years later. She had a well-publicized romance with former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, when he was 30 years her senior, before she ran for district attorney. (Legendary San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen called her the “Speaker’s new steady.”)

Brown was a mainstay in California politics and was the Speaker for the California State Assembly for 15 years. The relationship, which ended years before Harris ran for office, went on to haunt her for years. When one reporter for SF Weekly asked about it on the campaign trail, she called it “an albatross around my neck.”

But the public was still curious. For most of her political career, she was a single woman with no kids and therefore a figure that’s hard to compute in the American patriarchal imagination. The criticism could make her cagey. She sometimes took offense when asked about her personal life, preferring to talk policy.

Still, Harris earned her political chops during an auspicious time for young California Democrats. Her stint as DA coincided with now California governor Gavin Newsom’s time as mayor of San Francisco, notable for his defiant legalization of gay marriage in 2004. The two have been in something of a sibling rivalry ever since, vying for political power statewide and nationally.

Harris then went on to become attorney general of California. She won against a Democratic opponent who had strong backing from law enforcement, many of whom remembered her refusal to pursue the death penalty in the police officer’s murder half a decade earlier. That criticism pushed her slightly to the right in her reelection in 2014. Just as the nation was waking up to police abuses of power and protesting the deaths of unarmed Black men at the hands of law enforcement, Harris’s office declined to back statewide legislation that would require police to wear body cameras or take away investigations of police shootings from local district attorneys.

Even as Black Lives Matter blossomed in her hometown of Oakland, Harris—who often tells a touching story about going to protests as a toddler and screaming for “fweedom”—saw her star continue to rise. In 2017, she entered the Senate and quickly became known for bringing her prosecutorial muscle to the confirmation hearings of Trump’s cabinet members.

By 2019, when she launched a campaign for president, her life’s work—law enforcement—was suddenly cast in the new, punishing light of calls to defund the police. Even though she modeled the campaign after Shirley Chisholm’s historic 1972 run for president, some inopportune timing meant that Harris couldn’t quite nail down a definitive platform. Her younger sister Maya, a veteran policy adviser who worked with Hillary Clinton, was a close adviser, and reportedly counseled that her sister steer her messaging away from policing. The messaging was confusing. Kamala was a cop who once locked people up for drug offenses but now bragged, much to her father’s dismay, about her Jamaican heritage and smoking weed. What did she really believe?

Despite a memorable debate performance that saw Harris personally confront Biden about his record on school desegregation, Harris’s first presidential bid was beset by mixed signals and fundraising woes. Most damaging was that Harris couldn’t nail down a concrete narrative about her political identity. Not just about who she was, but why she made certain decisions. Instead, her critics did the defining for her.

After she was selected by Biden to run as vice president, Harris was relieved of the responsibility to frame her own narrative. The results were sometimes cringe.

She’s also been saddled with some of the administration’s toughest issues, including voting rights and investigating the root causes of migration from Central America. While touring Guatemala, she gave a press conference that signaled her willingness to be a team player, even if it meant publicly disavowing an issue that had no only shaped her policy agenda, but also, as the child of immigrants, her personal life. “Do not come,” she said, repeatedly, during that presser, to anyone thinking about making the harrowing journey north. That press conference happened around the time as her first big introduction to American audiences during a primetime interview with Lester Holt at CBS, which was widely viewed as a disaster. She then mostly disappeared from the media spotlight, which some observers chalked up to her perfectionist tendencies.

Now that spotlight is brighter than ever. There’s no more hiding. She’ll be asked about her wardrobe and her recipes and her family. It’s unforgiving and, yes, probably unfair. But she has to deliver a clear, consistent message about every issue to show the chasm of policy differences between her and the Trump ticket. “We have 107 days until Election Day,” she said in her statement on Sunday.

Buckle up.