Richard Vogel/AP

In 2020, Sharon Giovinazzo, who is blind as a complication of multiple sclerosis, wanted to vote independently—and in person. She knew that electronic voting machines in Little Rock, Arkansas, then her home, were her only option.

Giovinazzo called an Uber to take her and her guide dog to the polls. The first three canceled on her. Giovinazzo, now CEO of LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco, knew that was a possibility.

“You lose that autonomy of just being able to go where you want, when you want,” Giovinazzo said, “and do what you want.” (As an unfortunate bonus, the accessible voting machine at her polling place wasn’t working—someone had to help cast her ballot despite her efforts.)

“You lose that autonomy of just being able to go where you want, when you want,” when you’re discriminated against.

As more and more states clamp down on mail-in voting—in Texas, for instance, where it’s difficult to vote by mail, ballots can be rejected if a poll worker thinks their signature doesn’t match one on file—there a greater urgency to make it physically practical to get to voting booths, even among people comfortable with absentee voting. In addition, a joint survey by the US Election Assistance Commission and Rutgers University following the 2022 midterms found that nearly half of disabled voters prefer voting in person.

Scheduling paratransit to the polls is one option—but in rural areas, that can also be more challenging than it should, says Michelle Bishop, manager of voter access at the National Disability Rights Network.

“Even if you can get a pickup to take you to your polling place, you have no idea when you’re going to need a ride home,” Bishop said. “That’s something that you would have had to have scheduled well in advance.”

RideShare2Vote was founded by Sarah Kovich and her daughter Paola in 2018 in Texas to help Democrats and left-leaning independents vote. In addition to utilizing regular cars, RideShare2Vote rents out accessible vans to take voters to the polls free of charge, including in rural areas. Drivers also receive training to understand voting rights. “Every voter that a [Rideshare2Vote] driver has ever taken has been able to cast a ballot with us,” Kovich said. “No one’s been turned away.”

The organization operates in more than a dozen states—mostly Republican strongholds and swing states. But, again, those plans need to be etched out before voting day—and its budget only lets it take some 12,500 voters to the polls in a given election year.

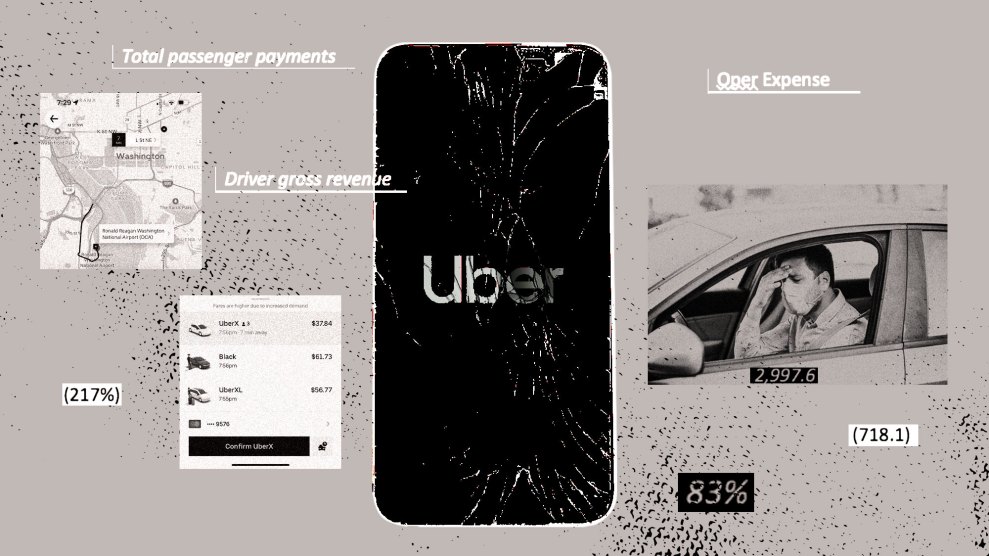

In an ideal world, rideshare apps like Lyft and Uber could be a great alternative for people without ready access to paratransit. But the issue remains that drivers cancel on riders (which has been the subject of court settlements), and accessible vehicles are not readily available. One wheelchair user seeking to vote in person also shared a video with Mother Jones of a driver refusing them a ride because of their wheelchair. A 2018 report from New York Lawyers for the Public Interest found that, when requested, barely half of New York City riders received accessible vehicles from Uber—and below five percent for Lyft.

Training drivers not to discriminate against disabled people, and having accessible vehicles available, should be universal to rideshare firms. But it isn’t.

In statements to Mother Jones, both Uber and Lyft said they didn’t tolerate discrimination, and that they encourage disabled riders who have experienced it to submit reports. But it happens too often to report every time, and disabled people often face stigma for filing complaints, especially ones under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Other organizations have also partnered with ride-share companies to get people to the polls: this year, NAACP is partnering with Lyft to do just that for Black voters, who often face disenfranchisement. Asked how NAACP would work with Lyft to make sure Black disabled voters weren’t turned away, its national mobilization director, Tyler Sterling, said in a statement that the organization is “working closely […] to ensure their drivers are equipped with the necessary cultural competency” to help all Black voters looking to participate.

The expense of transportation means there’s no simple, perfect solution to help disabled people vote, said Bishop, of the National Disability Rights Network. Bishop says that makes it crucial to fight for a voting system “where we have just a whole menu of options for voters, and they can figure out what makes it work for them”—a challenge not only due to expenses, but both ableism and rising voter suppression.