On an unusually warm Thursday afternoon three weeks before Election Day, Joe Sheehan, a Democratic candidate for the Wisconsin Assembly, took me on a tour of his hometown of Sheboygan, an industrial city of 50,000 on Lake Michigan that calls itself the “Malibu of the Midwest” and is best known for its bratwurst. We stopped on Superior Avenue, a wide, tree-lined street that runs east-west across the city, from the lake toward the countryside.

“This is one district,” Sheehan said, pointing to the north side of the block. He walked 10 feet to the other side of the street. “This is another district. Ta-da, gerrymandering!”

Both sides looked identical, with maple and oak trees and two-story homes festooned with Halloween decorations and blue Harris-Walz yard signs. But in 2011, when Republicans drew new redistricting maps in secret to give themselves lopsided majorities in the legislature, they split the city of Sheboygan in half at Superior Avenue to attach both parts to the surrounding redder rural areas. Sheboygan had been represented by a Democrat in the Assembly in all but four years between 1959 and 2011, but ever since it has elected two Republicans, becoming a poster child for the gerrymandered maps that were regarded as among the worst in the country.

Last year, however, a progressive majority took over Wisconsin’s Supreme Court and struck down the skewed lines. The Republican-controlled legislature reluctantly passed new maps proposed by the state’s Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, which gave both parties a roughly equal chance of winning control and dramatically increased the number of competitive races. Democratic-leaning Sheboygan, which Joe Biden carried by 8 points in 2020, became whole again and is now one of the 15 seats Democrats need to win to regain control of the state Assembly (the lower house) for the first time in a decade and a half.

“Wisconsin was not a democracy by any meaningful definition of that word. This year, Wisconsin is a democracy. Whoever gets more votes, will probably get more seats.”

Sheehan is running for office for the first time at 66. He served for 20 years as the superintendent of Sheboygan-area schools, but came out of retirement to help Democrats regain control of the Assembly after new maps were put in place. “That’s a huge part of me running,” he told me. “Previously, when the city was split up, Democrats had a really hard time winning because their vote was split up. Now their vote isn’t.”

Sheehan has a bushy salt-and-pepper mustache and describes himself as a Tim Walz Democrat, “not formal, more of a coach-teacher type.” His first TV ad shows him in the classroom talking, much like Walz, about the importance of free breakfast and lunch for kids, which his opponent, GOP Rep. Amy Binsfeld, voted against. He’s the type of home-grown and authentic candidate that Democrats believe can help end 13 years of hard-edged GOP control of the state.

While the presidential race consumes virtually all of the country’s political oxygen, there’s a tremendous amount at stake at the state legislative level in 2024 as well. Democrats are vying to retake or maintain control of legislative chambers in more than half of the presidential battlegrounds, including Wisconsin, Arizona, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

The new lines in Wisconsin represent a sea change in one of the country’s most important toss-up states. Democrats have won 14 of the past 17 statewide elections in Wisconsin, but Republicans control 65 percent of seats in the Assembly and 67 percent of seats in the state Senate, just short of a supermajority in both chambers. “For over a decade, we had maps in Wisconsin that made it more likely that Republicans would have two-thirds supermajority than Democrats would have a majority in an almost perfectly 50–50 state,” said Rep. Greta Neubauer, the Democratic leader in the Assembly.

This seemingly voter-proof advantage gained through gerrymandering gave legislative Republicans a green light to entrench their power through tactics like voter suppression, dark money, and stripping Democrats of power, while the size of their inflated majorities allowed them to block, with little accountability, popular policies on issues like abortion rights, health care, gun restrictions, and education. “For more than a decade, Wisconsinites knew the victor in the state legislative races in advance,” said Ben Wikler, chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party. “Wisconsin was not a democracy by any meaningful definition of that word. This year, Wisconsin is a democracy. Whoever gets more votes, will probably get more seats.”

In 2022, there was just one true toss-up Assembly race in the state, according to the Milwaukee-based journalist Dan Shafer, despite competitive elections for virtually every statewide office. Now, under the new lines, there are 10 districts that Biden won by 2 points or less. “We absolutely believe there’s a path to a Democratic majority here,” said Neubauer, while admitting that picking up 15 seats to regain control “is a lot to flip in one year.” (Only half of the state Senate is up this cycle, so 2026 is the earliest it could flip to Democrats.) But even if Democrats simply reduce the GOP’s advantage, that will bring the legislature more in line with the purple nature of the rest of the state. “What the gerrymander did was prevent the voters from holding Republican legislators accountable for the decisions that they were making in Madison,” said Neubauer. “I really do see these fair maps starting to restore the democratic process in Madison and hopefully increasing bipartisan work.”

Wikler believes that legislative candidates like Sheehan represent a “secret weapon” for Democrats up and down the ballot this year. Democrats recruited candidates in 97 of the state’s 99 Assembly districts and the increase in the number of competitive races could boost Democratic turnout, he argues, which could make the difference in a state that is regularly decided by 20,000 votes or less in presidential elections.

“There’s always these moments in the Fast & Furious movies when Vin Diesel hits the nitrous and pulls into the lead, and that nitrous super boost this year for Democrats could be the state legislative races,” he said.

The progressive group Run for Something, which recruits candidates for downballot races, calls it the “reverse coattails” effect. The group studied seven battleground states in 2020, including Wisconsin, and found that when Democratic state legislative candidates ran for office in districts where Republicans previously ran unopposed, the Democratic vote share for the top of the ticket increased by anywhere from 0.4 percent to 2.3 percent.

Wikler predicts there’s a small but significant number of potential Democratic voters in the state who are disillusioned by national politics but will vote in state races because of issues like Wisconsin’s 1849 abortion ban or cuts to public schools. “It’s not a huge number, but it doesn’t take a huge number of people to tip statewide elections in Wisconsin,” he said. “If you turn out a few hundred more voters in a handful of key state legislative districts that could add up to the statewide margin of victory in the presidential race in the state that tips the entire Electoral College.”

He’s betting that candidates like Sheehan can break through stereotypes of the party in a way that Harris might not be able to do, like the one splashed on a giant red-and-white sign I saw when I drove into Sheboygan: “Kamala wants to do to Wisconsin what she did to California.”

Few voters will perceive Sheehan as a California liberal, however. His yard signs are green, the color of his beloved Green Bay Packers, and the campaign material he gives to voters has the team’s schedule on the back. “That’s one thing they won’t throw away,” he said.

As Sheehan knocked on doors in Sheboygan, his crossover appeal became evident—but so did the difficulty of automatically translating his support to the rest of the Democratic ticket. He turned off Superior Avenue and passed a gray house adorned with colorful Halloween decorations, including a severed head that looked all too real. Darbie Magray, a welder who wore a purple-and-blue tie-dye sweatshirt, yelled out that she’d already voted by mail for Sheehan. She is the type of swing voter Democrats need to win if they hope to flip the legislature and carry the state—a registered Independent who is skeptical of Trump but still not sold on Harris. “I don’t like Donald Trump at all,” she said, as her son precariously climbed on the porch railing to attach a head on a skeleton. But she wasn’t a fan of Harris, either. “I don’t like some of the things she’s done either,” she said. “I don’t like that she let all these immigrants come over.”

Magray wouldn’t say which candidate she supported for president, but she openly expressed her admiration for Sheehan, citing his support for public schools and vow to protect abortion rights. “I just think he’s the best candidate,” she said.

Sheehan said he’s knocked on 3,000 doors in Sheboygan and talked to 40 voters who said they’ll vote for him and Trump. “What they told me is, ‘Joe, it sounds like you’re listening to me and want to get along,’” he said.

“If you turn out a few hundred more voters in a handful of key state legislative districts that could add up to the statewide margin of victory in the presidential race in the state that tips the entire Electoral College.”

After knocking on doors, he took me to his favorite bratwurst restaurant, Northwestern House, a former brothel next to the railroad tracks. The owner gave him a dap as he entered and said he’d voted for him. So did a number of other elderly white patrons who didn’t look like your stereotypical wine-drinking, latte-sipping, Zoom-watching Harris voter. Sheehan ordered a double brat sandwich with butter and brown mustard, a Sheboygan staple, with a side of tater tots—the type of meal that would put most candidates to sleep. “You got a familiar face,” a man visiting from Janesville told him. “You’re either running for something or a car dealer.” When Sheehan said he was running for Assembly, the man told him, “You got a friendly face. Good luck.”

With so much polarization in politics these days, maybe a friendly face eating brats is exactly what could swing the balance of power in a battleground state that will be decided by the smallest of margins.

In 2010, as Democrats were preoccupied with passing Barack Obama’s legislative agenda in Washington, Republicans blindsided them by picking up nearly 700 state legislative seats. This “shellacking,” as Obama called it, gave the GOP the power to draw four times as many state legislative and US House districts as Democrats in the subsequent redistricting cycle, including in critical swing states like Wisconsin.

Democrats have been playing catch up at the state level ever since. They unexpectedly picked up chambers in Michigan, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania in 2022, but remain at a significant disadvantage, with Republicans controlling 56 legislative chambers compared to 41 for Democrats.

The States Project, an outside group that supports Democratic state legislative candidates, is focusing on nine states in 2024: flipping GOP-held chambers in Arizona, New Hampshire, and Wisconsin; defending new Democratic majorities in Michigan, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania; preventing GOP supermajorities in Kansas and North Carolina to preserve the ability of Democratic governors to veto legislation; and winning a Democratic supermajority in Nevada that could override the vetoes of the state’s Republican governor.

Major national developments, including Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election at the state level and the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, have underscored the importance of state legislative races. “2024 is potent combination of state legislatures posing a risk to a free and fair presidential election and state legislatures having been handed a fundamental constitutional right,” said Daniel Squadron, co-founder of the States Project.

In addition to the weighty issues state legislatures decide—from voting laws to abortion rights to gun control to book bans—their balance of power is often decided by a handful of votes. New Hampshire Republicans won a majority in the state house by 11 votes in three races in 2022. Control of the Virginia House of Delegates was determined by a coin flip in 2017.

Despite the outsize importance of state legislative chambers—and the fact that Republicans have used their power over state politics to roll back so many hard-won rights—Democrats continue to pay less attention to these races than Republicans.

On October 10, one day after the Harris campaign announced that it had raised a staggering $1 billion, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC) warned that it was $25 million short of money needed for “essential voter contact tactics,” including funding for TV ads, mailers, digital outreach, and door-knocking programs, despite receiving $2.5 million from the Harris-Walz ticket.

“The latest data from the field shows our party’s collective effort to win key state legislative races could fall short this cycle without a significant increase in financial support to close essential funding gaps in the final weeks of this election,” wrote DLCC President Heather Williams. “Right now, our internal data suggests we may be on an eerily similar trajectory to the 2020 election outcomes—when Democrats narrowly won the White House and took full control of Congress, yet lost more than 100 Democratic legislative seats and two chamber majorities in the states.”

Those resources are especially vital because Democrats are less likely to vote for downballot races than Republicans, who tend to vote straight-ticket for all contests. That could end up costing Democrats control of pivotal swing chambers. “It’s no secret we are still working to tell the story of what I would say is an ‘and’ strategy,” said Williams. “Democrats need to care about what is happening in the White House and the Congress and the states.”

When I asked Squadron, a former New York state senator, if state legislative races were getting enough attention amid the presidential race, he responded, “The answer is an emphatic no! Enough attention relative to the ability to impact electoral outcomes? No. Enough relative to their impact on people’s lives? No. Enough attention relative to their role in preserving a liberal democracy in this country? No.”

Even though many Democratic candidates, including Harris, have focused their campaigns on issues like abortion and fair elections, a shocking number of Democratic donors and voters still don’t seem to understand that states are far more likely to decide these issues than the federal government, especially in the wake of recent Supreme Court decisions embracing states’ rights.

“Structurally, state legislatures don’t get the attention that top of the ticket races do,” said Squadron. “There continues to be a fundamental belief, especially among Democrats, that the federal government is a greater source of harm or improvement in people’s lives than state governments in a way that just isn’t accurate.”

But deep-pocketed GOP donors do understand the importance of investing at the state level.

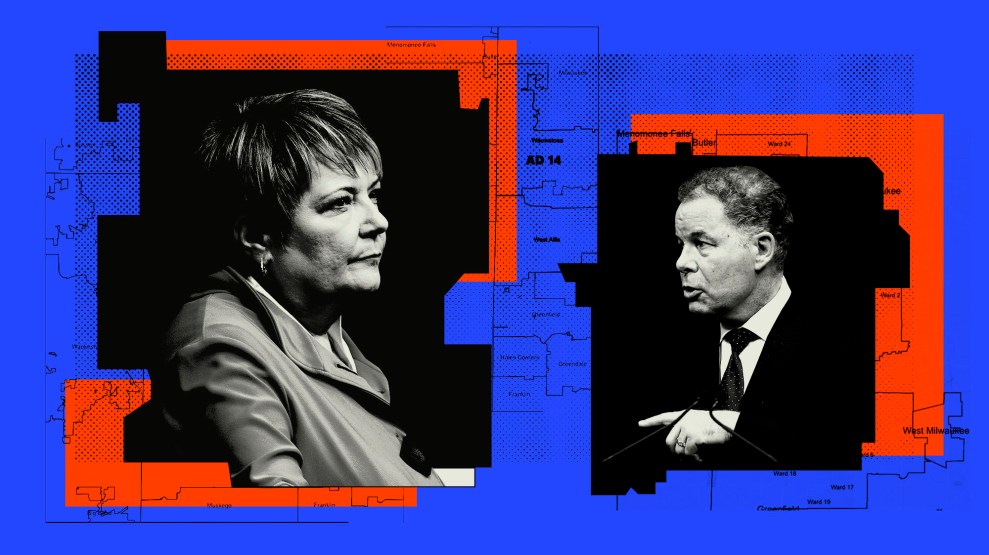

Two GOP megadonors, Elizabeth Uihlein (whose family has bankrolled much of the election denial movement) and Diane Hendricks (the state’s richest woman), donated $4.5 million last month to Wisconsin Assembly Republicans, giving them a $2.5 million advantage over Assembly Democrats. Republicans changed Wisconsin law in 2015 to allow unlimited donations to legislative campaign committees—one of the many ways in which they undermined the democratic process under GOP Assembly Leader Robin Vos to entrench their power. “We have no one who can write us a $1 million check,” Neubauer said. “That puts us at a competitive disadvantage.”

But what Democrats lack in money, they hope to make up in old-fashioned shoe leather. Compared to past elections, where GOP control of the legislature was predetermined, Neubauer said she’s “seen incredible enthusiasm in Sheboygan and the other districts that were significantly gerrymandered under the old maps. People are thrilled to have the opportunity to compete in a competitive election at the legislative level.”

After I visited Sheboygan, I drove an hour north to Green Bay, where Harris was holding a campaign rally across the street from Lambeau Field. Wikler spoke first to the crowd of 4,000 supporters. One of the biggest applause lines of the night came when he referenced the state legislative races. “We finally have fair maps in the state of Wisconsin!” he said to cheers. “We can make Robin Vos the minority leader in the state Assembly and Greta Neubauer the majority leader.”

Few voters nationally could name these people, but everyone at the rally in Wisconsin understood the stakes.