President Donald Trump in the Oval Office on December 22, 2017, displaying his signature on the Republican tax overhaul package.Mother Jones illustration; Evan Vucci/AP

As Donald Trump campaigns to be a dictator for one day, he’s asking: “Are you better off now than you were when I was president?” Great question! To help answer it, our Trump Files series is delving into consequential events from the 45th president’s time in office that Americans might have forgotten—or wish they had.

President Donald Trump was lying profusely about his administration’s most notable achievement, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), even as he sat down to sign the bill into law in 2017, a few days before Christmas.

“As you know, we had the largest tax cuts in our history just approved,” he remarked at the “rush-job” Oval Office signing ceremony, from which the usual gaggle of fawning Republican legislators was excluded—the souvenir pens were instead offered to the lucky few reporters on hand. “This is bigger than, actually, President Reagan’s.”

Uh, not even close—though it was the biggest corporate cut. Thanks to his tax bill, Trump went on, corporate America was already “making tremendous investments. That means jobs; it means a lot of things. And we’re very happy. So that’s AT&T, Boeing, Sinclair, Wells Fargo, Comcast, and now many other companies.”

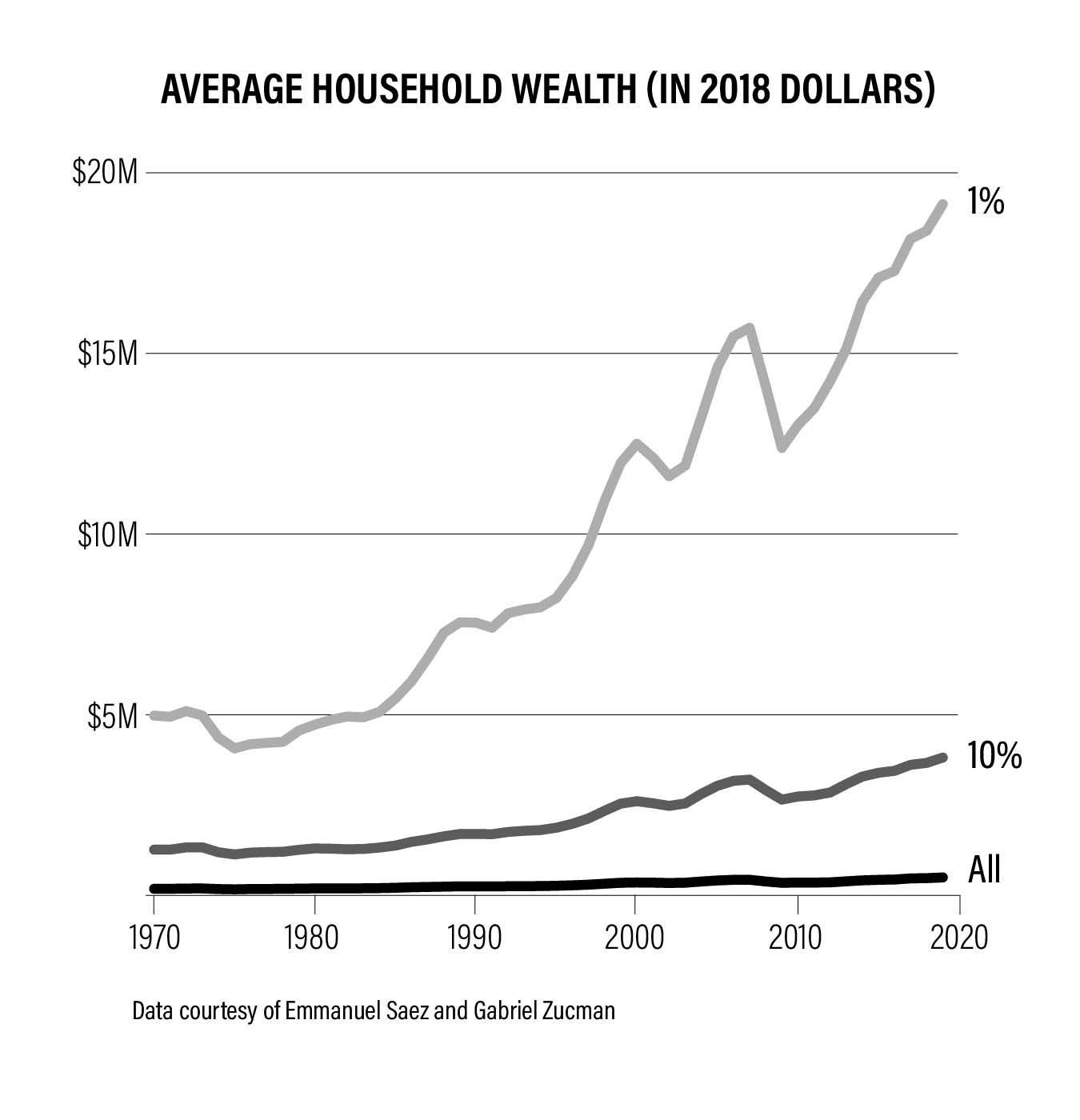

The rich are feasting on America’s economic pie. Republican tax cuts have set them on a steep upward wealth trajectory, far and away from the “little people.”

The executives sure were happy. The legislation slashed corporate income taxes dramatically, from 35 percent to 21 percent. Not surprising, given that, according to the nonprofit Public Citizen, more than 7,000 lobbyists—on behalf of a who’s who of Corporate America—helped hammer out the bill’s details. That’s 13 lobbyists per lawmaker.

And what did these joyful companies do with their windfall? Build new factories? Hire more workers? Raise wages? Stimulate economic growth? There was some of that, sure. But the cuts came “nowhere close to paying for themselves,” the New York Times later reported, and have added more than $100 billion a year to the deficit.

Just about every Republican president since Reagan has relied on the same debunked theory to advance tax cuts for corporations and wealthy Americans. It’s called supply-side (or “trickle-down”) economics. The idea is that if we give rich folks more money, they’ll invest, build companies, and create good jobs. The economic benefits will then trickle down to what the late New York heiress Leona Helmsley—whom the press nicknamed “Queen of Mean”—allegedly called the “little people.” (That fun fact emerged during testimony at her 1989 trial for tax evasion—where she was found guilty. Helmsley died in 2007, famously leaving $12 million to Trouble, her pampered little dog, but nothing to two of her four grandchildren.)

Trump’s corporate cuts, predictably, trickled not down but up. As I wrote in my 2021 book, Jackpot, the first instinct of executives and board members after Congress passed the TCJA was to enrich themselves:

S&P 500 firms spent a record $806 billion in 2018 buying back their own shares on the public markets. The Harvard Business Review notes that senior executives, paid largely in stock and stock options, use buybacks to manipulate share prices “to their own benefit” and the benefit of “investment bankers and hedge-fund managers” who are further enriched “at the expense of employees, as well as continuing shareholders.”

Buybacks are indeed marvelous for executives and Wall Street bankers. By reducing the number of outstanding shares on the market, they drive up the stock price to the benefit of major shareholders. But they’re bad news for workers, who have traditionally benefitted from excess corporate profits and their reinvestment in operations and equipment, which tends to strengthen the business and bring new jobs. Buybacks also can be bad for long-term investors, because they encourage a short-term mindset in the C-suite and can be used to mask a firm’s underperformance.

Notably, every one of the firms Trump praised by name during the signing ceremony notched major buybacks soon afterward: Sinclair’s board greenlit $1 billion in the months to follow. Boeing’s board approved $19 billion, and numerous reports have blamed the company’s aircraft safety fiascos in part on its lust for buybacks. (Late last week, the company announced it would lay off roughly 17,000 people, or 10 percent of its workforce.)

On Trump’s watch, Congress doubled the gift and estate tax exemption. A rich couple can now leave their kids $27.2 million without paying one dime in tax.

AT&T repurchased $692 million worth of its stock in 2018 amid reports that it had been laying off workers and closing call centers—and completed nearly $2.5 billion in buybacks the following year. Wells Fargo was in for almost $41 billion, and Comcast shelled out $8.4 billion for buybacks and dividends (which it juiced by 10 percent).

“We give stock to corporate managers to convince them to create the kind of long-term value that benefits American companies and the workers and communities they serve,” Robert Jackson Jr., who then served on the Securities and Exchange Commission, declared in a June 2018 speech. “Instead, what we are seeing is that executives are using buybacks as a chance to cash out their compensation at investor expense.”

Even when wealthy businesspeople are incentivized to “create value,” results may vary. “A friend of mine, Bob Kraft, called me last night, and he said this tax bill is incredible,” Trump remarked at the signing.

“He owns the New England Patriots,” Trump said, “but he’s in the paper business too. And he said, based on this tax bill, he just wanted to let me know that he’s going to buy a big plant in the great state of North Carolina, and he’s going to build a tremendous paper mill there.”

I looked up that “tremendous” paper mill. Trump, as usual, botched the details. The plant is in Catawba, South Carolina. Kraft’s company, New-Indy, took it over in September 2018, after which it became a total nightmare for the community—generating more than 47,000 complaints of noxious odors “similar to rotten eggs, dirty diapers or other foul smells,” including from people in North Carolina.

The Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy released an analysis of whom Trump’s new tax proposals would benefit. It probably isn’t you!

Another big deal, Trump said, were the estate tax changes in the tax bill: “Something very important to me,” he said (if you can imagine anyone not named Trump being important to Trump), were “the family farmers and small-business owners who lost their business because of the estate tax. Most of them won’t have any estate tax to pay. It will be a great thing for their families. You can leave your farm to your family. You could leave your business, your small business to your family—not even so small, because the numbers are pretty big here.”

They are big! The TCJA doubled the gift and estate tax exemption and pegged it to inflation, which means, as of 2024, a well-heeled couple can leave $27.2 million to their heirs without paying one dime in tax.

But that won’t save any “family farms.” That’s a well-worn Republican talking point that amounts, fittingly enough, to a heap of cow manure. Back in 2017, a researcher with the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) pointed out that only 50 small farms or businesses would be on the hook for federal estate tax that year (a “small” business can have up to $40 million in annual revenues and 1,500 employees), and most would likely have other assets, such as stock, that could be liquidated if need be to cover the tax. Existing law, she also pointed out, allows estates “to spread their payments over a 15-year period at low interest rates.” America’s farmers were never in danger.

The Reagan tax cuts enacted in 1981 and 1986 added up to biggest break for wealthy Americans since 1920. The top marginal rate owed in 1981 on the uppermost income tier of the nation’s highest earners—anything exceeding $215,400 for a couple (about $760,000 in today’s dollars)—was slashed dramatically, from 70 percent when Reagan took office to 28 percent the year he left. Congress also reduced the gift/estate tax, more than tripled the lifetime exemption—the amount parents can leave their offspring tax-free—and trimmed taxes on capital gains and corporate profits.

And what was the outcome of all this largesse? Another snippet from Jackpot:

In 2012, a researcher at the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service sought to determine whether the Reagan cuts and other reductions in marginal income tax rates over the prior sixty-five years had benefited the overall economy. He came up short. The tax cuts did not appear to be correlated with more robust saving, investment, or productivity growth. They did, however, appear to be associated with rich people making a lot more money than before. There was no evidence that the cuts expanded America’s economic pie, the report noted, “but there may be a relationship to how the economic pie is sliced.”

You might even say the very rich pigged out on the pie. The Reagan cuts set America’s most affluent citizens on a steep upward wealth trajectory, soaring them far and away from the “little people.”

Supply-side economic arguments would later enable George W. Bush to slash taxes further. Among other provisions, the 2001 and 2003 bills he signed reduced the top income tax rate, then 39.7 percent, to 35 percent—lower even than today—and began phasing out the estate tax, which Congress briefly repealed in 2010, only to reinstate it the following year.

“High-income taxpayers benefitted most from these tax cuts, with the top 1 percent of households receiving an average tax cut of over $570,000 between 2004-2012,” explains a CBPP analysis. By 2010, the report notes, the Bush cuts resulted in a 1 percent bump in annual after-tax income for the poorest fifth of US families, whereas the top-earning 1 percent enjoyed a 6.7 percent increase.

Unfair? Sure. But did the Bush cuts ever deliver the economic results supply-siders promised? Nope. “Evidence suggests that they did not improve economic growth or pay for themselves, but instead ballooned deficits and debt and contributed to a rise in income inequality,” notes the CBPP.

Fast forward to 2024, when Trump told a crowd of “rich as hell” donors he’ll give them more tax cuts if elected to a second term. They cheered! Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders made a Facebook video.

Trump has said he wants to cut the corporate income tax further, too—to 15 percent. (Kamala Harris proposes raising it to 28 percent, still well below the pre-Trump rate of 35 percent.) And he keeps introducing new, ill-conceived, tax proposals on the campaign trail—mostly regressive—adding to a haphazard plan that the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects will cost the federal government, depending on economic conditions, anywhere from $1.5 trillion to $15.2 trillion over a decade. (The Harris plan, the group projects, would cost between zero and $8.1 trillion.)

On October 7, the nonpartisan Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy released an analysis of whom Trump’s tax proposals would benefit.

It’s probably not you.

Love it or hate it, at least now you better understand the Republicans’ dirty little secret: Supply side economics, cutting taxes on the wealthy, doesn’t work. It has never worked. It’s complete bullshit. But alas, it’s the sort of bullshit that refuses to be composted.