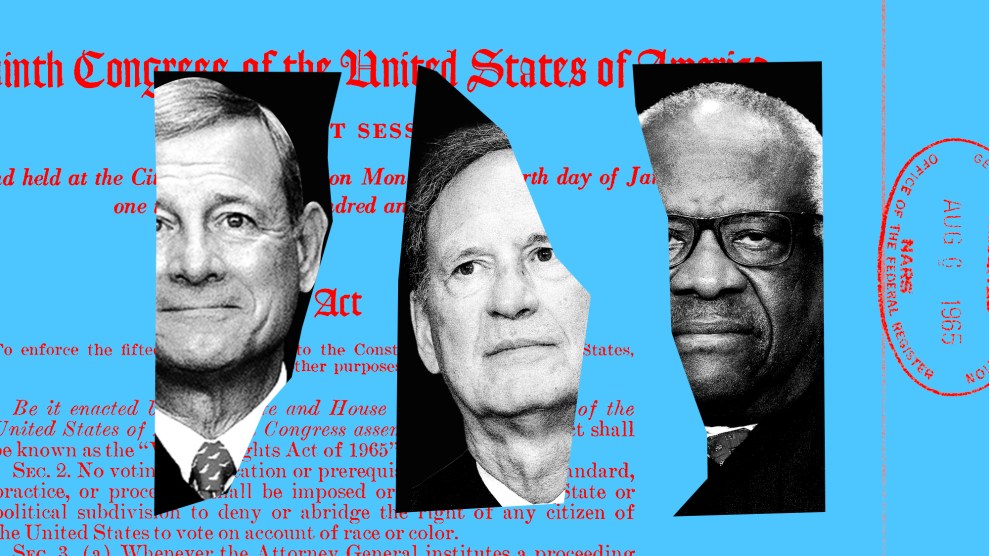

Mother Jones illustration; Mark Wilson/Newsmakers/Getty; Win McNamee/Pool/AP

The Supreme Court will begin a new term on Monday, in which it is set to hear pivotal cases about transgender rights, our environment, and gun violence. But the term’s biggest blockbuster could be a case that not only hasn’t yet been filed, but is still just a concept.

That’s because in the next three months, the justices may be asked to inject themselves into the late stages of the 2024 election. If presented with such an opportunity, this could be the term that the Supreme Court elects Donald Trump.

Four years ago, Trump and his allies attempted to overturn his 2020 loss from the White House, while his allies controlled legislatures in the critical states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Georgia, as well as key institutions like the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Trump’s coup failed not because he and his allies lacked power, but because President Joe Biden’s margin of victory was big enough that some allies—including his own attorney general and most Senate Republicans—refused to use that power to illegally keep Trump in office. This year, Trump does not hold as many levers of power. But a faction of his political coalition, the GOP-appointed 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court, controls one of the most important.

Conservative justices have obvious Trump sympathies and clear incentives to see him back in the White House.

The high court has already been a player in this election. Last term, the justices ensured that Trump’s attempt to steal 2020’s election could not disqualify him from the presidency, issuing a decision assuring he would appear on every ballot. The court delayed Trump’s criminal trial over his attempted coup, then granted him broad immunity from criminal prosecution, preventing damaging courtroom revelations from emerging before voting. In August, the court used its shadow docket to allow Arizona, a key swing state, to require proof of citizenship with voter registration forms at the request of the Republican National Committee.

But perhaps least known—and yet, most important—was Moore v. Harper, a 2023 ruling in which the court set the stage for the next Bush v. Gore scenario by holding that the justices themselves would have the last say when it comes to questions over state-level election rules and disputes.

Twenty-four years ago, the Supreme Court stepped into Florida’s contested presidential race and handed the presidency to Republican George W. Bush. Five Republican-appointed justices overturned the Florida Supreme Court and halted the state’s recount effort. Four Democratic-appointed justices dissented. At the time, the majority acknowledged their election meddling was an exception, not the rule: “Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances,” the majority promised, calling it their “unsought responsibility” to resolve the case.

The decision didn’t just pick the president—it also, in installing George W. Bush, allowed him to reshape the Supreme Court. As younger lawyers, three of the current GOP-appointed justices aided Bush’s Florida legal team in the run up to Bush v. Gore. Another, Clarence Thomas, was part of the decision’s majority. Five of today’s justices personally and significantly benefited from the consequences of the ruling, including by accepting jobs or appointments under Bush’s administration. Not only have none of these conservative jurists expressed remorse about their actions or the decision, with Moore v. Harper they have in fact normalized the court’s meddling so that if the opportunity arises, they can do so again.

In November 2000, John Roberts flew down to Florida to help Bush’s lawyers prepare to argue before the Florida Supreme Court. Six months later, Bush nominated Roberts to the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, and in 2005, tapped him to join the Supreme Court as chief justice. Brett Kavanaugh likewise flew to Florida, where he helped monitor Volusia County’s recount. Kavanaugh went on to work in the Bush White House before the president nominated him to the DC Circuit in 2003; he was confirmed in 2006. The youngest member of today’s court, Amy Coney Barrett, was just a few years out of law school when she was sent to Florida by her Bush-backing law firm to help his legal team with research and briefing. (During her Supreme Court confirmation hearings, she said she didn’t recall the particulars of the work.)

Thomas, the only justice remaining on the court from that time, has been under a cloud of scandal for over a year now due to ethical conflicts, including participating in cases pertaining to the 2020 election despite his wife’s political activities and her support of Trump’s attempts to stay in power. Ginni Thomas’ ties to GOP powerbrokers presented similar issues in 2000, as she was drawing up a list of people to serve in a Bush administration at the same time her husband was providing a critical vote to secure his win.

Were it not for Bush v. Gore, the court as we know it would not exist. As a result of Bush’s appointments of Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, Thomas’ fringe views found growing support in a new far-right majority. Today, that bloc also includes Justice Neil Gorsuch, who first became a federal judge in 2006, thanks to a nomination from President Bush. So much of the conservative legal movement’s success can be traced back to the ruling—and there’s no reason to think the justices involved regret it.

Bush v. Gore was supposed to be a one-off because it saw the Supreme Court step out of its usual lane to overturn a state court decision on state election administration, which is generally left up to the states. But last year, in Moore v. Harper, the Supreme Court opened the door to similar interventions whenever it decides a state court has “transgress[ed] the ordinary bounds of judicial review” at the expense of state legislative power. With voting underway for 2024, this vague and untested standard provides a new opening for the court to meddle in state election matters.

“The size of this loophole is unknown at this point,” warns Jessica Marsden, an attorney at Protect Democracy. “But there are cases percolating up that will raise this issue and test the size.” As Marsden explained during a Supreme Court preview hosted by the Center for American Progress, such cases could affect “either how voting happens in November or even which ballots get counted.”

In the critical battleground of Pennsylvania, the state Supreme Court is currently deciding whether to count mail-in ballots that, while valid, do not conform to every rule, such as missing a handwritten date on the envelope. If the state Supreme Court allows such ballots to be counted, under the new rationale of Moore v. Harper, the US Supreme Court could find justification to intervene and toss out tens of thousands of ballots in the most contested state in the nation.

Marsden also pointed to Nevada, another battleground, where the Republican National Committee has tried to roll back a policy of accepting mail ballots that arrive after Election Day. “If Nevada were the decisive state and they hadn’t resolved this issue ahead of the election,” Marsden said, “I don’t know that I’m optimistic that in that situation that the Supreme Court would decline to reach in and decide.”

Still, Marsden sounded a note of cautious optimism about the slim chances of another Bush v. Gore. “It’s actually very hard to tee up an issue for the Supreme Court that would be outcome determinative,” she said. Indeed, the best way for the Harris campaign to keep the Supreme Court out of the race is to win by enough that their interventions would be futile.

It may be hard to create the conditions where the court’s Republican-appointed justices are in a position to decide—but the Trump campaign and its allies are certainly trying. Four years ago, the courts acted as a bulwark against Trump’s attempts to overturn the election, including the Supreme Court, which rebuffed his challenges. And for good reason: the cases were extremely weak. “The challenges to the election outcome last time were last ditch efforts by a few fringe actors like John Eastman,” says Alex Aronson, executive director of Court Accountability, a progressive group pushing Supreme Court reform. Trump’s rag-tag team was clearly going to lose, and even allies like Bill Barr, his own attorney general, jumped ship. But this time, Aronson notes, there is a “more serious cohort of lawyers and funders behind these challenges.”

The conservative legal movement’s success traces back to Bush v. Gore.

Barr, for example, is on the board of a group involved in voter suppression lawsuits, including one of the challenges to Pennsylvania mail ballots. Attorneys in the funding orbit of Leonard Leo, the dark money patriarch of the conservative judicial movement who helped select and confirm the GOP-appointed justices, are behind suits to purge voter rolls and change voting rules. And the Republican National Committee itself is strategically litigating around the country to make it harder to vote and to invite courts to throw out ballots. When the Supreme Court allowed Arizona’s requirement that new voters show proof of citizenship, they handed a win to the RNC and a law firm backed by Leo. The people and groups behind the legal attacks on the 2024 election are in the mainstream of the conservative movement, which could induce the justices to take up the opportunities those lawyers will bring to the courts.

The conservative justices not only have obvious Trump sympathies, but clear incentives to see him back in the White House. Two of them, Alito and Thomas, are widely believed to want to retire, but would only do so under a Republican administration. And while their movement to remake the legal landscape is well underway—from making guns more available, abortion unavailable, religion pervasive, and environmental regulation impossible—their goals would be a fait accompli under a second Trump administration. Meanwhile, Harris is openly campaigning on reforming the Supreme Court: It’s not only the justices’ legal project that could hinge on the outcome of the election—it’s also their jobs.

Back in March, the court issued an anonymous opinion reversing Colorado’s decision to keep Trump off the ballot on the grounds that he had mounted an insurrection, a disqualification discussed in the 14th Amendment. But Roberts—who was later revealed to be the author—and four other conservatives went much further to protect Trump from 0ther legal challenges under the 14th Amendment.

There was no need to take this additional step, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, joined by the Democratic-appointed justices, except to help an “oathbreaking insurrectionist” become president. She prominently quoted from a dissent in Bush v. Gore: “What it does today, the Court should have left undone.”

For some on the court, Bush v. Gore is a reminder of what it should not do. For other justices, it may now be a roadmap for what it could do.