Each Friday, we pull articles from our archives to propel you into the weekend.

“I knew no black people—young or old, rich or poor—who didn’t feel injured by the experience of being black in America,” wrote Roger Wilkins in his 1982 biography. In 1973, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his editorials about the Watergate scandal. In the 1960s, he worked in the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. His close personal mentor was Thurgood Marshall. Wilkins was also a regular contributor here at Mother Jones.

He wrote for this magazine in 1992 a piece titled “White Out.” In it, he describes “an even bigger hurdle” than 1960s segregation, to his mind: “the power of whites to define blacks.” (Throughout, when quoting, I am adopting Wilkins’ use of a lowercase “b” for Black; our magazine’s style now, and my belief, is that an uppercase Black is better suited.)

He describes how he’d noticed, from talking with his white students (Wilkins taught at George Mason), that “many suburban racial attitudes have actually rolled back to something like the fifties.” He remembers how in more “innocent” days, before integration, racism would be thought of not as systemic, but as “individual.”

“We believed that the power to segregate was the greatest power that had been wielded against us,” he writes. “It turned out that our expectations were quite wrong. The greatest power turned out to be what it had always been: the power to define reality where blacks are concerned and to manage perceptions and therefore arrange politics and culture to reinforce those definitions.”

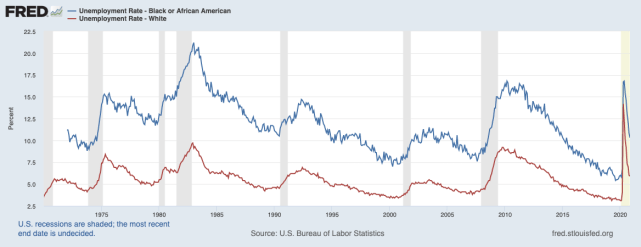

It reminded me of the argument made in a recent essay for this magazine that so-called “cultural” concerns cannot be so easily cleaved from the material. They are intertwined. For example, Wilkins notes that the Black unemployment rate in the United States in the early 1990s had never gone below 10 percent since the early 1970s.

I looked up the current numbers. That’s no longer true. It has gone below 10 percent. But, still, look at the vast gulf over the past 50 years between the Black unemployment rate and the white one.

Except at the very peak of the pandemic, the Black unemployment rate is close to double the white one. As the economy has pseudo-normalized into its active inequality, that gap has reasserted itself.

Wilkins, in discussing racism, never separates these two concerns; he wants to change material policies: “For me and other black people, there is nothing to do but stay the course. That means, more than anything else right now, fighting to get decent jobs for poor blacks, fighting for support for poor families and for good education for black children,” he writes. And he wants to enact cultural change. “What can I say to decent white people? I think the best answer is what so many whites invariably preach to us—self-help… We can’t save white folks’ souls. Only they can do that.”