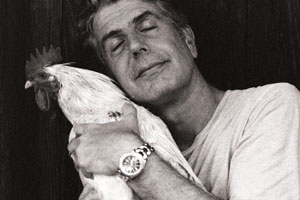

Chris Buck/Corbis Outline

In his first book, Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain exposed the saucy, sometimes sordid, sex-drugs-and-rock-and-roll lifestyle of the restaurant business. He also guaranteed that no self-respecting foodie would eat sushi on a Monday ever again. He parlayed that success into No Reservations—the rare Travel Channel show to have a parental advisory regarding sexual innuendo—which serves up a heady mix of fine dining, street food, and irreverent and often touching ruminations on love, war, punk rock, and whether bone marrow is better than sex. It is, he admits, the best job in the world. Recently, Bourdain and crew married their other great love, film, to the show’s premise: An episode in Rome was shot in La Dolce Vita black and white, complete with letterboxing, dubs, and fierce sunglasses. He’s also used his bully pulpit to mount a defense of foie gras—watch his segment on it and you might change your mind—and scathingly criticize vegetarian activists. Yet in his latest book, Medium Raw, he also takes on the industrial meat complex, reveals his strategy for keeping his daughter away from McDonald’s (cooties!), and embraces the democratization of haute cuisine—as well as dishing serious disdain for food demigods like Alan Richman, Alice Waters, and Alain Ducasse.

Mother Jones: It seems odd that a chef could come out of a punk-rock sensibility, if being a chef is all about taking orders from customers and more senior chefs.

Anthony Bourdain: There are people with otherwise chaotic and disorganized lives, a certain type of person that’s always found a home in the restaurant business in much the same way that a lot of people find a home in the military. They’re looking for order in their lives. They’re looking for absolutes. They’re looking for a quantifiable kind of statistics—a way to measure whether they’re doing well or badly. They’re looking for a group whose respect they want and crave. Call it a family or a military hierarchy. Everything important I learned, I learned as a dishwasher.

MJ: It also seems kind of counterintuitive that cooking shows would become so popular. After all, the viewers on the couch can’t taste or smell the food. What do you attribute this trend to?

AB: People like looking at food. I think it’s a sensual experience. People will relate it back to their own personal memories. But ultimately it’s become a form of popular entertainment, a human drama like any other. Will Contestant No. 1 burn their hands and have their dreams shattered and go back to Palookaville, or not? Chef friends and I debate all the time: Why us? Why now? How did this happen? They never cared about us before. I grew up at a time when you’d see a movie first and then go to dinner and talk about movies. Now, people just go right to dinner and talk about the next dinner they’re having, or the dinner they had last week.

MJ: So, after 100 episodes of No Reservations, are you worried you’ll run out of material and be parsing the food of the greater Duluth area?

AB: No. I could do one show after another in China for the rest of my life and still die ignorant. There’s a lot of places left to go. We’re doing a Congo show next year. It’s a big world with lots of great stuff in it.

MJ: The most moving moments in your show are not necessarily when you’re with the great lights of the international food scene but when you’re with Laotian villagers, or kids in the slums in Buenos Aires. How did that mix of high-low sensibility come about?

AB: It never occurred to me to do otherwise. Very often, the best chef in town started out living in a working-class section of town or came up hard. I like telling stories, and I tell stories that interest me. It would be boring to have to go to nothing but the best restaurants. That would be a misery to me.

MJ: In Medium Raw, you take on some of America’s most revered restaurants, like Thomas Keller’s Per Se, for sucking too much of the fun out of dining.

AB: I called that chapter “It’s Not You, It’s Me” for a reason. I’m really kind of wrestling with the fact that I am very likely perceiving that kind of dining experience a lot differently than most people would, and I’m kind of bemoaning the loss of my own ability to enjoy it. I mean, The French Laundry was maybe the greatest restaurant meal of my life. But I think it says a lot, mostly unflattering about me, that I can’t really enjoy this incredible, luxurious meal at Per Se.

MJ: Certainly here in San Francisco, it seems that the big movement is to have a more casual atmosphere, no matter how fine the food. Do you think that’s part of the democratization of the food movement?

AB: Well, we’re seeing that everywhere. We’re seeing that in Paris also. Generally, I welcome that trend. But without places like Per Se and French Laundry, where will these chefs opening these more democratic, sort of customer-friendly, moderately priced casual places, where will they learn? Those great kitchens, that’s the training grounds for the chefs that Keller needs. But also, more importantly, they’re the training grounds for [Momofuku chef] David Chang. The kind of cooks he needs.

MJ: You know, David Chang upset a lot of excessively touchy San Francisco foodies when he criticized our prevailing cuisine as a bunch of “figs on a plate.”

AB: To which I’m outraged, honestly. I mean, David loves San Francisco. You know, he’s a funny guy. The humorlessness with which it was taken was so appalling, and that he was actively boycotted by a few chefs who saw themselves as defending the honor of San Francisco, was just tragically stupid.

MJ: You lay into Alice Waters on several fronts, but mainly for not being the greatest ambassador for the sustainable food movement, because she seems to be so out of touch with the economics of ordinary people. Do you think that the future she talks about is impossible?

AB: Well, I think it is possible in increments. I think she fetishizes food—which is a good thing. But it’s a good thing for people like me, and a certain foodie elite, and for people who benefit from that kind of sexualization of food. I was with her in front of an audience of hundreds of people, and somebody asked an innocent question: “What would your death-row meal be? Your last meal on Earth?” And for all her talk about sustainability, Alice’s answer was shark fin soup! I think she was saying something about how sophisticated her tastes are. I think that makes her a bad spokesperson when you’re trying to win the hearts and minds of people who are struggling to pay their mortgage, have two jobs, kids, no time or little time to cook, much less plant a garden in the backyard. You can’t make people feel bad about themselves, or like idiots, or unsophisticated, or guilty about their ability to live up to Alice’s standards. It’s like having, you know, Alec Baldwin or Barbra Streisand supporting your political candidate. It’s great for preaching to the converted, but I don’t think you’re winning any hearts and minds out in the heartland.

MJ: And yet you briefly laid into Mark Bittman for showing people how to make paella in an aluminum pot because they don’t have the perfect cast-iron pot. Is that any different than Alice Waters thinking everyone can—

AB: Well, he claims to know everything. And I think that the most fundamental aspect, the most beloved aspect of paella, is the crispy, crunchy stuff on the outside, or that outer layer. It seems disrespectful to a great dish to tell people in a presumably authoritative way, “this is acceptable,” when you’re basically removing the best thing about it right off.

MJ: Do you think the locavore movement is a better way of integrating communities with their restaurants?

AB: Yes! Listen, I’m all for it. I would like to see people more aware of where their food comes from. I would like to see small farmers empowered. I feed my daughter almost exclusively organic food.

MJ: You devote almost a full chapter to the evils of the industrial meat , but by the end you come back with a pretty full-throated attack on vegetarians. Do you think Americans should be eating less meat?

AB: I do. I think our ratio of protein to vegetable and starch is distorted. It probably would be a good thing if we moved more toward the Asian model. I admire vegetarians who refuse to eat nothing but vegetables in their homes, but I also admire those who put aside those principles or those preferences when they travel. Just to be a good guest. One of my few virtues—I don’t have a lot of them—would be a deep sense of curiosity. I’m interested in how other people live in other places; I’m interested in other cultures. I know that it’s possible to travel and to politely decline, or let people know up front that you don’t eat meat. But there are a lot of places that are just not going to get that. It shuts you off from a human dimension. And it goes against my grain.

MJ: It seems like your unhappiness with vegetarians comes from a few different beliefs: that you kind of fear the nanny-state concept; that it’s often a luxury of the affluent; that they prioritize animal rights over human misery…

AB: Yeah, or human joy, for that matter.

MJ: …And that they either try to force their views on others or rend the social fabric when they refuse the hospitality of carnivores.

AB: I admire vegetarians who refuse to eat anything but vegetables in their homes or communities, but I also admire those who put aside those principles or preferences when they travel. I consider one of my few virtues—I don’t have a lot of them—but one of them would be a deep sense of curiosity. It’s inconceivable why anyone would want to not experience as many colors in the spectrum as possible with our limited time on Earth. Sure, it’s possible to travel and to politely decline meat. But there are a lot of places where people are just not going to get that. It shuts you off from a human dimension. Even Jonathan Safran Foer talks about the “Thanksgiving Problem.” He’s chosen to offend Grandma. He understands it’s breaking a channel of communication, a shared experience, to put yourself outside the turkey experience. But at least he acknowledges that it comes at a cost.

MJ: You quit smoking two or three packs a day when your daughter was born?

AB: Yes.

MJ: Did you gain weight?

AB: A little, yeah.

MJ: I could imagine that, in addition the running around that chefs do, smoking and drinking also mitigates the great temptation to sample the food all the time.

AB: I don’t know. I haven’t seen my life improve in any tangible way at all since I quit. It became harder to smoke than to quit. And as a new dad, I feel some small responsibility to at least try to live a little longer for my daughter.

MJ: Once your daughter figures out that Ronald McDonald does not actually have cooties, how do you hope to keep her from the perils of food marketing?

AB: Well, we’ll just go to Italy if we have to. McDonald’s uses local meat in Italy, actually. My wife likes Italian McDonald’s. But I don’t want my daughter to see it; I don’t want to go near there. It’s like huffing crack in front of your kid.

MJ: Speaking of which, is there any shameful food that you give in to once in a while?

AB: I like the macaroni and cheese at Popeye’s. I’ll even eat the stuff at the Colonel, because I can slip in there late at night when no one’s looking. I’ll eat it in the street, huddled in a doorway, ’cause I don’t want my wife to see. I don’t want anyone to see.

MJ: In Medium Raw, it comes out that your wife and former assistant have used martial-arts training to ward off over-affectionate female fans. Did you ever think you’d be living that kind of life?

AB: No, absolutely not. There was no clue; even after Kitchen Confidential came out, I really believed for quite a while that I better keep my day job.

MJ: You said on a recent episode that you hadn’t learned really anything about writing, because essentially you write like you talk, which I found really interesting as an editor. There are roughly two camps of writers: extroverts who put their full personality down on paper very easily, and the more introverted who aren’t public persona types. I’m wondering if you’ve ever thought about that other kind of writer.

AB: I wish I could be like that. I wish I had the time. I wish I had the personality. I wish I had the skill. I wish I had the work ethic, the ability to concentrate. I’d love to be Don DeLillo. But you know, I’d love to be Bootsy Collins too.